Plant nerds rejoice! Gardeners who hike and who favor local natives will welcome the new Field Guide to Manzanitas.

Devoted to “nature's shrubby rock stars,” this book focuses on the 104 species and subspecies found in the California Floristic Province, which includes most of California as well as parts of southern Oregon and Mexico's Baja California. It does not cover the named cultivars that have been developed for gardens; the best resource for these is still online nurseries and other resources, including Las Pilitas Nursery, San Marcos Growers, and Theodore Payne Foundation.

Like any good field guide, this book shows various features for each plant described, such as habit (spreading, mounding, etc.), leaf, inflorescence (the complete flower head, including stems and buds), bark, and fruit. Photos of the key features are extensive, useful, and beautiful. The identification key relies on features that may be visible year-round, rather than on features such as flowers that are available for only a short season.

In addition, the ID key is place-based, which helps to narrow down which species you are seeing in the wild. If you were inspired to start gardening with natives to bring nature home, now you can identify the manzanitas you see on your hikes. Each species also has a range map that shows where it grows.

At a recent talk in Los Altos, Michael Vasey, one of the authors, said identifying manzanitas “can drive you crazy.” He and his coauthors have refined and tested the book's ID key over the years with many students in field workshops. In fact, it is even better than the manzanita key in the most recent Jepson Manual, which he also coauthored, he said.

Manzanitas are a foundation species, which means they “anchor ecosystem functions,” he said. For instance, 200 to 300 insect species have been observed on manzanitas, lots of birds “sweep through,” many animals find cover, and rodents harvest fruits and bury seed deep enough so it can survive fires.

Vasey proposed a “citizen science” project to test a hypothesis about the diversity of manzanita species. Some manzanitas have hefty burls that can resprout after fires (“spouters”) and can also reseed. Other manzanitas burn to the ground after fires and can regenerate only from seed (“seeders”). According to molecular-biology analysis, seeders can be split into two groups, a little clade and a big clade. Within a clade, they can hybridize freely. Between clades, hybrids seldom occur, but when they do, those plants are sprouters.

Within a stand of manzanitas in the wild, Vasey has observed that one of each type occurs: a big-clade manzanita, a small-clade, and a sprouter. To test the hypothesis, he is proposing that citizen scientists take photos whenever they go on hikes and encounter a stand of several different manzanita varieties, then send him the photos so he can determine if the hypothesis holds.

Interested observers can find more resources, add comments, or ask questions at the website manzanitas.backcountrypress.com

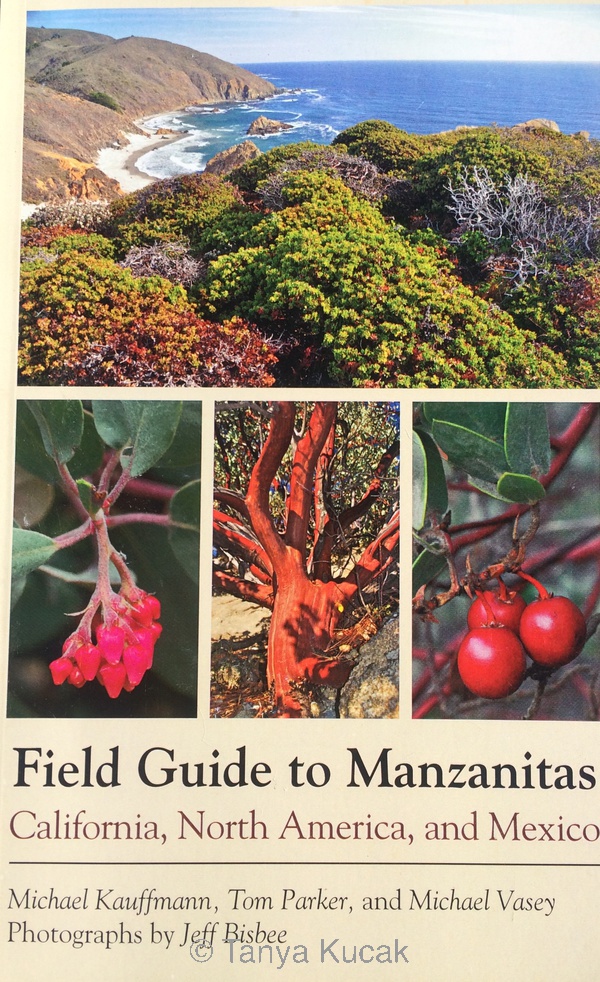

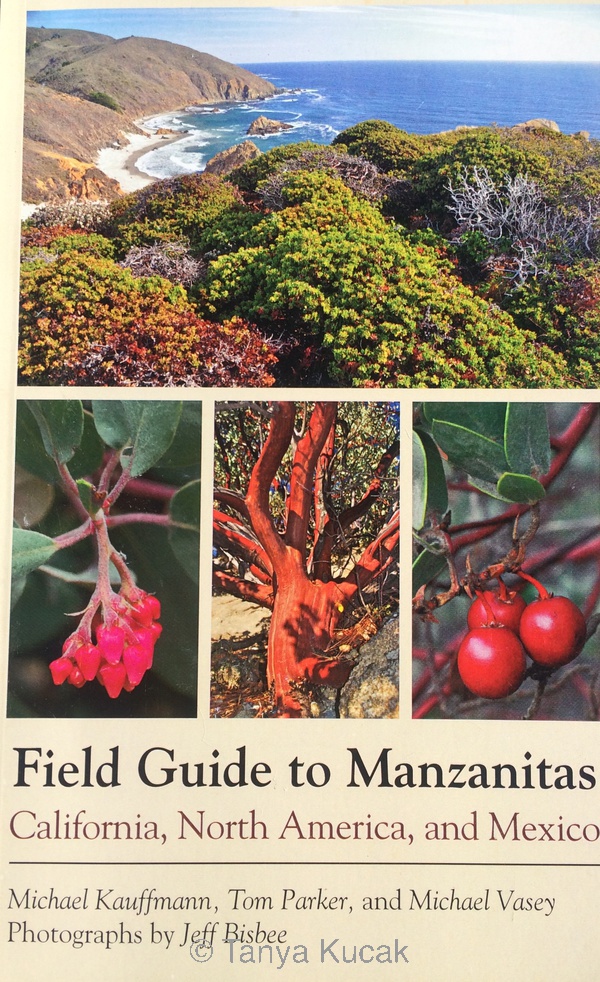

A Field Guide to Manzanitas: California, North America, and Mexico by Michael Kauffmann, Tom Parker, and Michael Vasey. Photographs by Jeff Bisbee. Kneeland, Calif.: Backcountry Press, 2015. 170p.

This book is a useful guide to manzanitas that are found in the wild. It includes a chapter on Manzanita Destinations where you can find key species, a list of species found in each county in California, and a list of other places where manzanita species are found. [no photo credit]

Santa Cruz Manzanita has boat-shaped leaves and sticky, depressed-globose fruit. In general, you can find a few fruit year-round on most manzanitas, even though the fruit is seasonally abundant and is eaten by lots of wildlife. (Photo: Tanya Kucak)

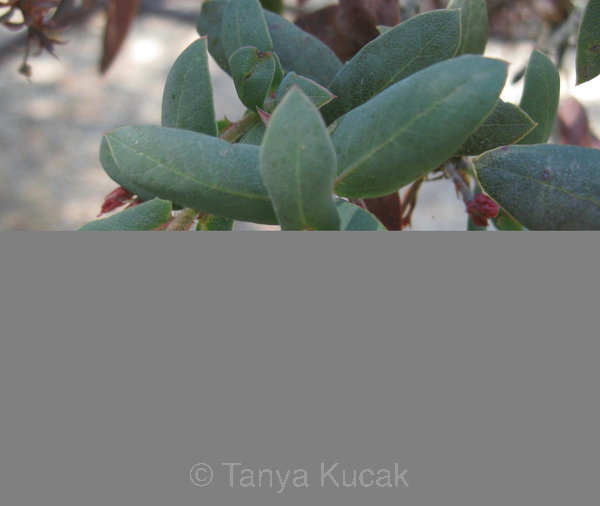

The immature inflorescences of Pajaro Manzanita have distinctive leafy bracts. Since these structures form soon after the flowers bloom each season, you are likely to see immature inflorescences on most manzanitas year-round. (Photo: Tanya Kucak)

© 2015 Tanya Kucak