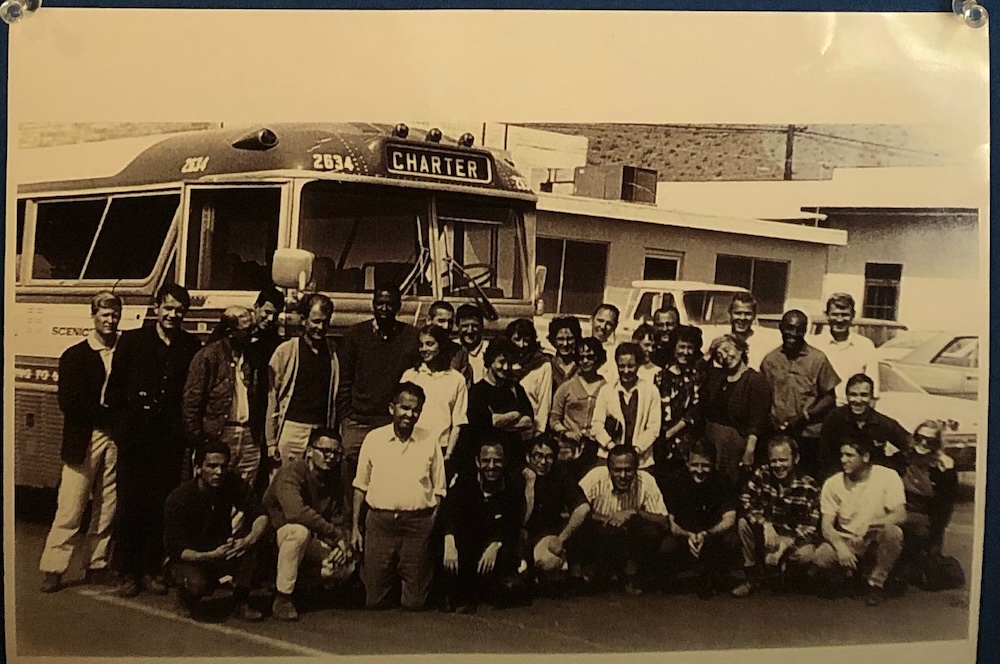

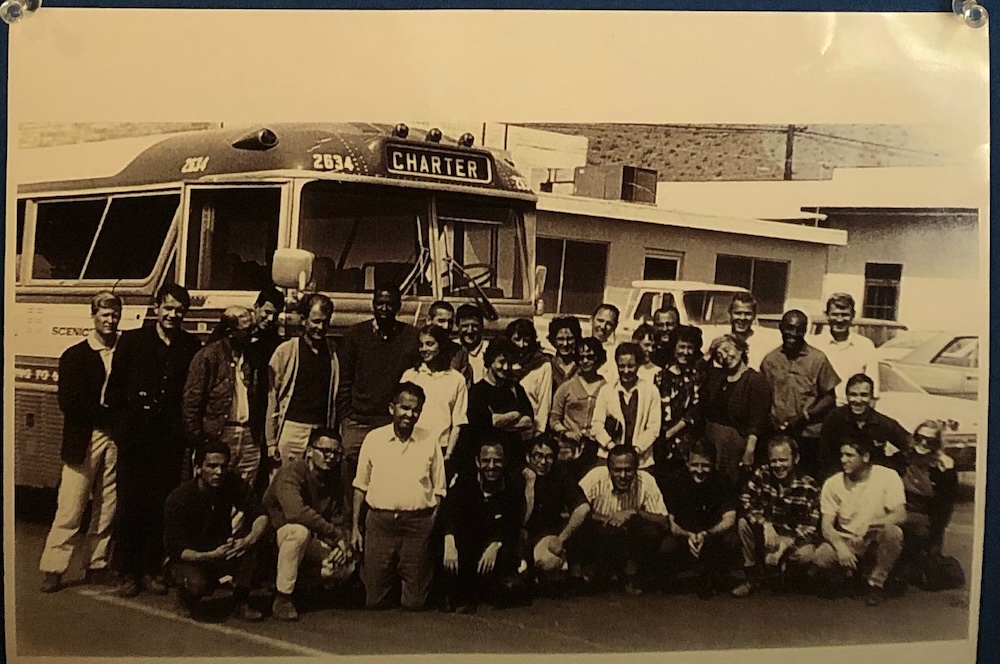

On March 13th, Dr. Martin Luther King called for clergymen from all over the nation to join in attempting a civil rights march on the 16th from Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery, Alabama – a march parallel to one crushed at Selma on March 7th by state troopers using billy-clubs, tear gas, and horses. Six Davis clergymen and one layman immediately responded and quickly obtained the support of their churches. After some delay and uncertainty due to political developments, the group received word on the 17th that the march now was scheduled for the 21st, and that people from all walks of life were urged to join it on the 24th and 25th. At the suggestion of two Davis laymen, efforts were begun on the 18th to gather a larger group for charter bus travel to Alabama. Only three days later at 3 p.m. on Sunday the 21st, twenty-seven people left Davis for Montgomery, to be joined by six more at Sacramento and one more in Montgomery.

The group was strikingly heterogeneous: ten women and twenty-four men, including nine clergy (and eleven belonging to no religious organization), six students, three professors, seven housewives, lab technicians, a rancher, a chemist, and others. The cost of the trip, some $4,000 was met entirely by voluntary individual contributions, $1,500 of which came from the thirty-four who made the trip.

And, as our bus pulled away, several SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) members led the thirty or so assembled friends and relatives in crossing arms, clasping hands, and singing “We Shall Overcome.” For many of us, the song could not have had, then, the meaning attached to it by later experiences, and yet there were tears in more than one person’s eyes.

The trip went swiftly. We quickly came into contact with and got to know each other as card games were begun, food was shared (“I have a loaf of bread and two fishes!”), and a guitar was brought out for group singing. As bus-fatigue and stiffness grew, some did exercises at the stops. At the same time that intimacy and esprit grew, however, so did awareness of entering southern territory, and apprehension. News of dynamite time-bombs found in Birmingham was given by our transistor-radio-carrying group newsman, broadcasting over his “Radio Free Selma” bus microphone. El Paso, Texas – two taverns refused service to a negro member of the group. Memphis – our first experience of general, open hostility in the depot. A saleswoman observed, “You’re the sorriest-looking bunch of white trash. They (the Negroes of Alabama) can have you!” Our new driver was cold where previous drivers had been friendly and helpful.

At 10:30 a.m. we crossed St. Jude’s muddy fields and jammed aboard a small, old bus together with a group from Indiana. Army helicopters and other planes, roared overhead as we drove past poor Negro homes whose occupants stood on the porches waving us on. Armed troops stood at short intervals along the road and scurried here and there in jeeps. Bright clear day. And then, at 11 a.m., there was the march led by the 300 seasoned veterans who had walked 38 miles from Selma. We thrilled and cheered as they went by, and then fell in behind, men on the outside, four abreast, arms linked. The organization was striking, from salt pills to sanitation, and from medical facilities to marshalls who sparked and ordered the marching.

State trooper cars cruised by with confederate flags on their front bumpers. A young white man rolled down his car window and forced loud, prolonged laughter. Another, standing perhaps 40 feet off from the roadside spat repeatedly and vehemently in our direction. For the most part, however, whites looking on in clusters seemed not so much aroused and angry as uncomprehending and afraid. But what was more important to most of us were the reactions of Negro spectators. While whites in passing cars and by the roadside stared in silence, Negroes waved, smiled, and cheered us on. One of many such scenes was remembered vividly: while the owners and guests of a restaurant – all white – stood and stared, Negress employees stood smiling and waving at another window.

After dinner, as we waited for transportation back to St. Jude for evening festivities, members of the group and of our host congregation spontaneously began to sing. With one of our ministers at the piano, the singing gathered momentum, inhibitions were eased, and soon some 30 Montgomery Negroes and California visitors were deeply involved in the rich emotionalism of freedom songs and spirituals. At 7:30 p.m. we left with reluctance.

Several of our group who tired and left early were offered a ride by a local Negro, who then insisted upon taking them for coffee. Yes, he explained, there was some opposition to the march within the Negro community, mostly from the small number of Negroes coopted to figurehead positions in the white power structure; but the striking thing was the high level of unity in support of the march. No, he did not think that visiting demonstrators would leave the Negro community in greater danger of white retaliation than before the march, for, he felt, the great show of support would both strengthen the Negro community and put the white community on notice that general retaliation would no longer be tolerated. Back at the church, we broke up into small groups, discussing the day’s events, then bedded down wearily on the pews and floor for the night. We later found out that the deacon and another member of the congregation stayed up all night outside of the church to guard our safety.

It is difficult to imagine just what the sight of our marching thousands meant to the onlooking whites. Both ahead of and behind us, we could see marchers in waves without end, striding through the capital’s main streets. An elderly white tugged at a minister’s arm, asked him what church he represented, and shouted, “If you were really a man of God you wouldn’t be here!” Another white, younger and tougher looking, pointed at one of our group and said, “I’m gonna get you.” Such incidents were exceptional. For the most part, whites looking on only stared uncomprehendingly at something they could not understand – at a world falling apart.

But none struck the mood of that hour as did Martin Luther King Jr. To a completely hushed crowd he proclaimed that Alabama’s – indeed the South’s – civil rights movement was now irresistably on the move, that it could not be turned back, and that Alabama would never be the same. The manifest truth of his words touched all of us. We were even more touched by King’s unique role in the movement at that hour. It was easy to imagine what a less temperate, a less christian leader might do in the position Dr. King held at the head of so powerful a crowd. And yet, he stood, heralded by all as the leader of the hour, proclaiming even with his triumph the continuing necessity of non-violence and of the highest moral dedication of fundamental Christian principles.

Again, the trip went swiftly, but not uneventfully. Our return route, differing from that used in getting to Montgomery, took us through Selma and the mid-section of Mississippi. At about 8:15 p.m. passing through Selma’s outskirts, we were spotlighted from off the road. A few hours later, as we went through Mississippi, we heard that a civil rights worker, Mrs. Viola Liuzzo, had been shot to death near Selma just minutes after we had passed the spot. Our shock and sadness at the news reinforced our commitment to the movement in which we had taken a small but meaningful part. Many of us had experienced great frustration at leaving Alabama when so much remained to be done. We now turned quickly to exploring plans for the future.

We were encouraged by certain things which emerged in reflecting upon our experiences. As one of our group who had worked for civil rights in the South five years before noted, there have been significant changes, and the Alabama Freedom March represents a great breakthrough. Five years before, it would have been unthinkable for Negroes to stand beside their white employers and wave encouragement to civil rights marchers. And where the Negro’s struggle in the South previously had been a kind of jungle warfare, grimly conducted in small groups against overwhelming odds for miserable returns, the movement now was an open, confidently bouyant mass movement.

We came away feeling that the southern Negro, as never before, is responding to the movement which seeks to gain civil rights equality for him. There can no longer be any doubt that meaningful contributions can be made by concerned people everywhere. As we travelled two days homeward, we spoke of this more than anything else: What can we do in the future? Plans were made for group discussion, appearances before other groups, fund raising, attention to patterns of discrimination in our own communities, and the possibility of future trips southward to help with voter registration or other aspects of the struggle. We know now as never before that there are worthwhile contributions to be made. We would like to think that our trip to Alabama is only a beginning.

(This narrative account reflects the combined efforts and reminiscences of the 34 valley people who went to Alabama. Since I was charged with drafting the account, responsibility for necessarily inadequate writing is mine alone – Gerald Friedberg.)

It has a detailed account of the Davis to Montgomery bus trip and the march. The preview includes all of this account.

There are also extensive stories about Andrew’s work for justice and peace in Central America - Nicaragua, Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Guatemala.