A point that has perplexed me somewhat is a reason for a story of the family. Of what significance can it be whether Greger Bjørnsrud came to America in 1874 and that he died in 1925, or any other fact relating to his children or his children's children? Any effort made to set down experiences of our family has no merit unless the reader can gain some form of inspiration and enrichment through his reading of these experiences. History can be a guide to worthy living or it can be accepted as an irrelevant assortment of facts with about as much meaning as a cigarette stub.

I haven't the slightest idea what kind of contribution this story of the family can or will make in the lives of those who read it. If no meaning can be found in its recitations, then its examination can be described as only a waste of time. It is our hope, however, that not too many will toss it aside and that something of value can be realized.

This saga of the Bjørnstads in America must necessarily be based on the memories of those who have chosen to contribute to its content. I have received material from Tilda, Amanda, Olga, Ida, & Iver of the second generation and Gerald, Royce, and Allen of the third. What they have written about themselves must be accepted as factual.

What is recorded about Papa and Mamma, Rudolf, Grace, and Betsy

is based strictly on the recollections of those of us now living.

Only the very elementary facts about them are available in written

form. This then is a story of the Bjornstads in America with a subscript:

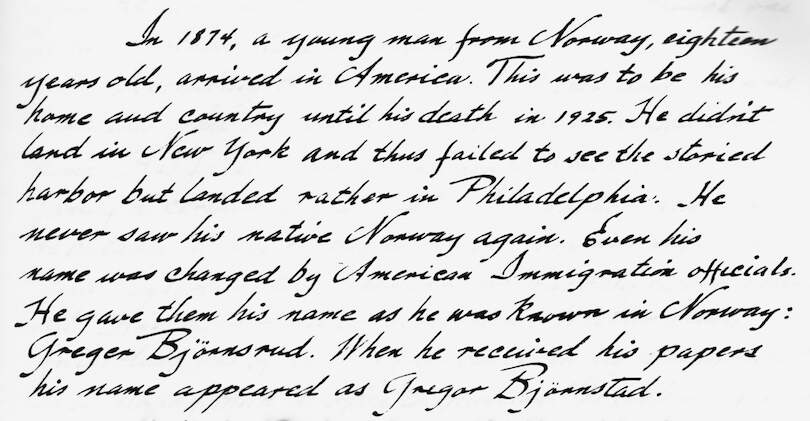

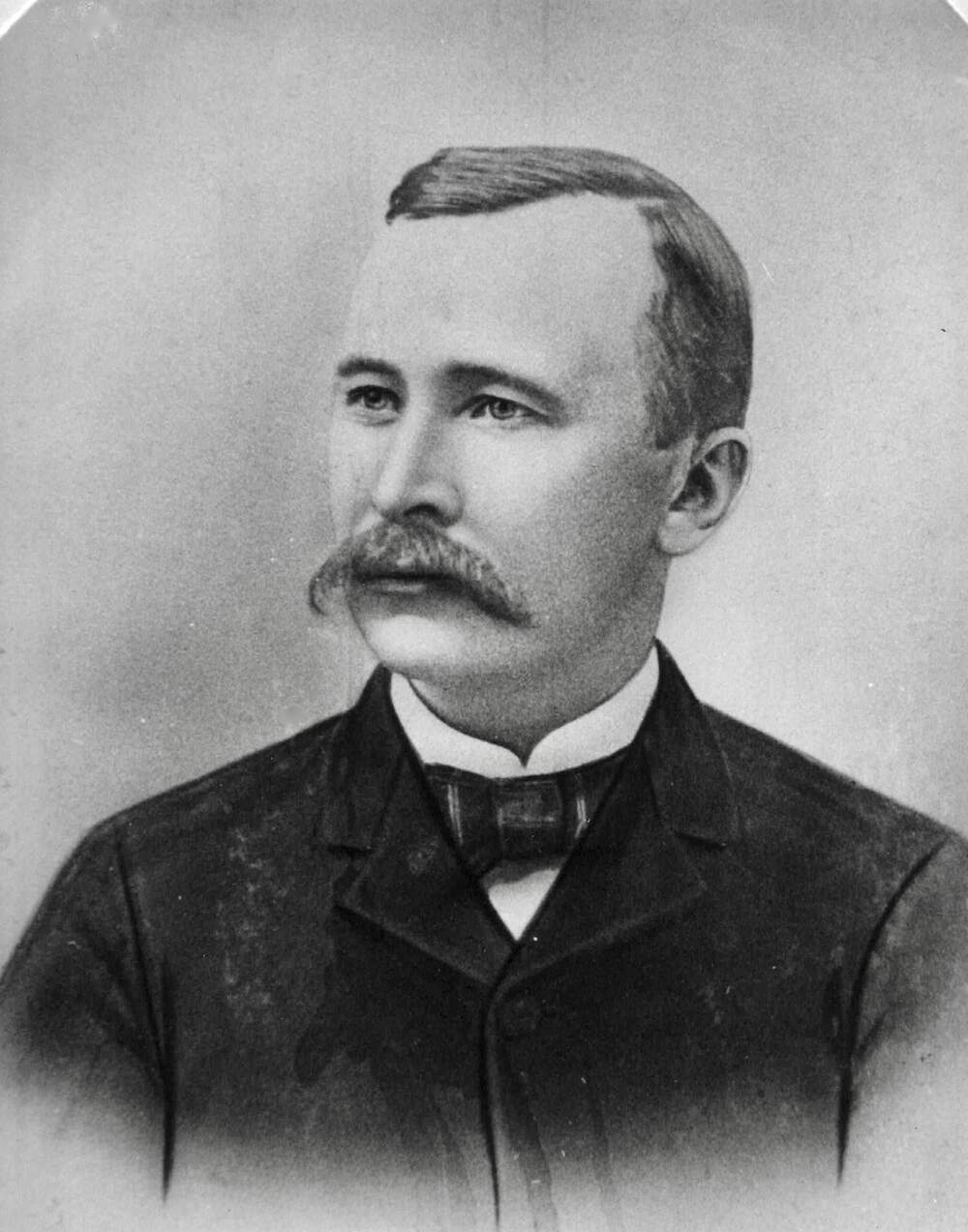

In 1874, a young man from Norway, eighteen years old, arrived in America. This was to be his home and country until his death in 1925. He didn't land in New York and thus failed to see the storied harbor but landed rather in Philadelphia. He never saw his native Norway again. Even his name was changed by American Immigration officials. He gave them his name as he was known in Norway: Greger Bjørnsrud. When he received his papers his name appeared as Gregor Bjornstad.

It is doubted if he really thought it was important that his name

had been changed. In those days, to leave your native land for the

New World was almost a complete severance of the old for the new.

There are millions of Americans today whose ancestors suffered

with loss of their old country family names as a result of the same

carelessness and inattention of American officials. To correct

such errors seemed to most immigrants not worth the price

in legal expense. Besides, most of them never acquired the price.

Gregor never challenged the error and thus his name remained

Bjornstad throughout his life as an American citizen.

Gregor was born on October 17, 1856, the fourth child of his parents, Ole Ivarson Bjørnsrud and his wife, Gro. He had four brothers and one sister, although one of his brothers died in infancy.

According to the standards of that day, he was born into what we would perhaps call a middle class home. His father was a landowner which gave the family a certain social status. His father also was reputedly highly respected in the community. He died, unfortunately, when Gregor was only eleven years old. His mother never remarried. Whether being fatherless was of any significance in his development as a young man is open to question. The lack of a father probably did influence the vocational aspects of his education that proved so necessary in his day.

His birth place was near what is now Uvdal on a piece of land called Bjørnsrudjordet in the Numedal valley.

Education in Norway in Gregor's time was a much different process than it is today or as we know it in America. A great deal was made of handskills that a person had to know in order to keep him warm and well clad and properly nourished. Weaving, spinning, and sewing and the preparation of food together with the care of milk cows and keeping the house clean was high on the list of things to learn before becoming an adult for young girls. For young men it was doing the heavy work on the farm and the acquisition of primary mechanical skills. To learn to read and write was only a part of a child's education. The skills, other than reading and writing and basic arithmetic, had to be taught by the child's parents or grandparents. It was probably in the vocational area of his education where Gregor found himself without a teacher. It was quite evident in his later years that he possessed only a slight knowledge of farming and the essential mechanical skills so important in that vocation.

About 1860, it became a point of law in Norway that each community had to build a building to house that part of a child's education relating to the basic disciplines of reading, writing, and arithmetic. Up to that time, such teaching was conducted in the homes of the children. The teacher went from house to house and the system was known as "omgangsskole." Perhaps in his early years, Gregor attended such an "omgangsskole." At any rate, he did learn to read and write and could perform in basic arithmetic. He certainly was not illiterate when he came to the United States and, as I recall, he was a great reader and kept well-informed, in current political events in particular. He was a great admirer of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson and was an ardent advocate of the League of Nations.

After his confirmation, which probably took place quite early in his life, he was taken by an uncle to the west coast of Norway and became what we would call a "peddler" of goods of various sorts. I can recall that he told me that they travelled through the fishing villages of that area as far north as the Lofoten Islands. Whether or not they prospered, I do not know. Presumably, they did make a living and perhaps this work provided the necessary money which gave him the opportunity to come to the United States.

From Philadelphia, Gregor headed for southern Minnesota where he knew he would find other Norwegian immigrants who knew the country and could give him assistance in helping him to adjust to life in the New World. He had three big problems. One was to find a job, he had to learn the English language, and he had to develop new friendships. He had no job skills, he didn't know the language, and he had no friends. It isn't likely that at his age he had any idea of the difficulties he faced.

He found only two jobs of which I have any knowledge. One was working I understand it was as a janitor, at a school called the Shattuck Military Academy. This was a school that prepared boys from wealthy and well-to-do families for entrance into eastern universities such as Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. This was an exclusive preparatory school and still is. It is probable that his association with this school, where nothing but correct English was permitted to be spoken, was of great assistance to him in acquiring a speaking and reading facility in English.

The other job I was told he had was as a dock clerk in a Fairbault hotel. He spent twelve years in Fairbault, Minnesota. This brought him up to 1886.

While it is true that Norwegians had been coming to America for decades since the founding of the Republic, the great surge of Norwegian immigration occurred after the Civil War. It was also in the post Civil War era that the great trek of homesteaders started westward toward the open prairies of western Minnesota and Dakota Territory. Gregor joined the trek westward and in the latter 80's showed up in the area of what is now Mitchell, South Dakota where his sister, Kristi, had settled with her husband, Halvor Lassegard. The Lassegards had departed Norway in 1879.

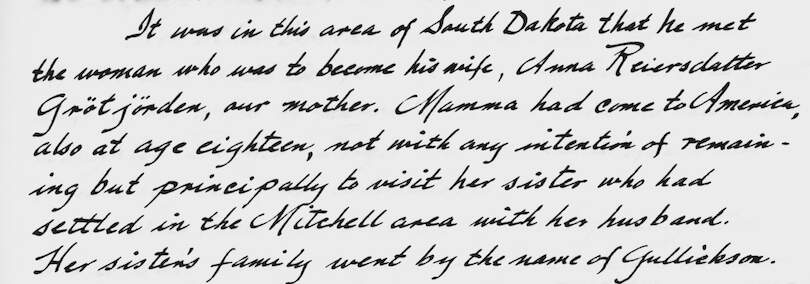

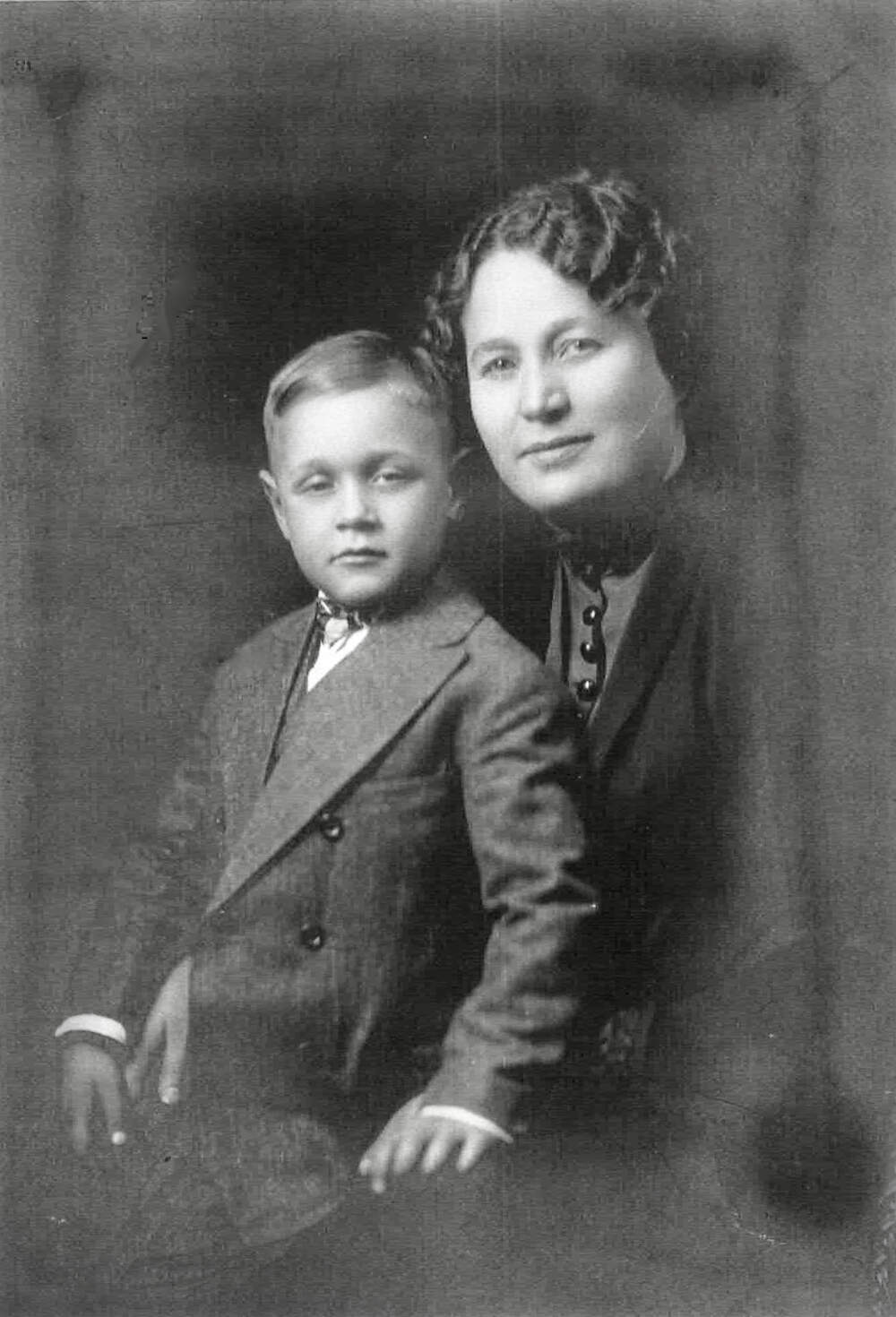

It was in this area of South Dakota that he met the woman

who was to become his wife, Anna Reiersdatter Grøtjørden, our mother.

Mamma had come to America, also at age eighteen, not with any

intention of remaining but principally to visit her sister who

had settled in the Mitchell area with her husband.

Her sister's family went by the name of Gullickson.

It was in this area of South Dakota that he met the woman

who was to become his wife, Anna Reiersdatter Grøtjørden, our mother.

Mamma had come to America, also at age eighteen, not with any

intention of remaining but principally to visit her sister who

had settled in the Mitchell area with her husband.

Her sister's family went by the name of Gullickson.

Mamma was born on the 16th of February, 1869.

Her parents were Reier Paulsen Gronnekakke who was born in 1830 and died

in 1910 and Birgit Larsdatter Gjermandrud, born in 1828 and died in 1924.

Her place of birth was on a farm near Uvdal in the Numedal valley

called Grøtjorden. It was the custom in Norway in those days to take

the name of the farm as a surname. Her name when she came to America

was officially Anna Reiersdatter Grøtjorden, however, she used

the name Anna Reiersen when she came to America.

She had one sister, the Mrs. Gullickson previously referred to who died in 1892, and two brothers. Her older brother, Paul, who was born August 12, 1861, came to America in 1879. As far as is known, he never married. According to the information once given me by Mamma, he died in Moorhead, Minnesota and news of his death appeared in a newspaper published in Norway. She didn't remember the date of his death.

Her other brother, Lars, was born September 13, 1866 and died in 1938. He married twice. His first wife, Gro, whom he married in 1890, died as did their daughter, Birgit. Birgit was seventeen years old when she died from tuberculosis.

Lars then married an Aagot Fjendingstad who is still living. A daughter, Bodil Selnes, is now living in Kongsberg as is her mother. Bodil has two children, Hanne and Lars. Hanne is married to a Thorbjørn Jagland and lives in Drammen. Lars is still very young, about thirteen years old.

Bodil was born in 1926. For many years, she has been employed in the Royal Mint in Kongsberg. Her husband, Harry, is connected with the Kongsberg Dairy. Bodil speaks and writes fluent English as does her daughter, Hanne.

Mamma had several relatives who left Norway for America before she did and Southern Minnesota and Upper Iowa shelters the homes of many of their descendants. The most familiar family names known to me are the Torstensons, the Gullicksons, the Solands, and the Steens and the Stensens. The latter two families lived in the Mitchell, South Dakota, area.

Of most interest to us was Mamma's grandfather, Lars Knutsen Bjermandrud, who was born in 1796 and came to America in 1858. He settled in the Lanesboro, Minnesota area. He died in 1878.

He was twice married. Mamma's mother was his only child by his first wife. He had several children, however, by his second marriage. Two of his daughters came to America, also: Margit, who became the wife of a Truls Soland and Anna, who became the wife of a man name Torstenson. Another daughter who we know about, Ragnild, remained in Norway and lived on a place called Myran. He also had a son, Ole Larson, who lived on a place called Kjemhus. Both Myran and Kjemhus are located in the Numedal valley.

We met two of Ole's descendants when we visited Norway in 1970, a Anna Nykelstue and a Margit Snøan. Margit is no longer living.

Another of Ole's descendants, Sigrid, came to America and married a man by the name of Amundson. A Mrs. Myrtle Day, her daughter, whom I have never met, but with whom I have corresponded, lives in Watford City, North Dakota. Myrtle has a brother living in Seattle.

Our mother and father were married in 1887 in the Rock Creek Lutheran church, a rural church near Mitchell, South Dakota. They then set out to homestead and chose a place about fifty miles west of Mitchell and across the Missouri River in an area that Mamma always referred to as the Sioux Indian Reservation. Their post office address was Oacama. Chamberlain was the nearest large trading post. At the time, there were only two settlers in this expanse of land and they settled five miles apart. The other settler was a Dane.

Why our mother and father chose this location to establish a home for themselves and their children can perhaps be explained only by the assertion that they didn't have good land judgement. But, with millions of acres to choose from, what sort of standards should they have had in mind? This area, even today, is not a good grain growing region but is adapted to cattle grazing and ranching which I am sure was not in their minds at the time of their settlement. But the land could be acquired for the asking and probably that was the only thought uppermost in their minds. Even if the land had been good soil, the rainfall was scanty and it was the continued drought that finally forced them to move to North Dakota.

This story would not be complete, however, unless some mention was made of the first home to house the Bjornstad family in America.

On the west prairies of what was then Dakota Territory, the only material one could use to build shelter for one's family and livestock was prairie sod. It was shelters of this type that our mother and father built. What they first did was to excavate a portion of a hill which provided a solid back wall and a portion of the sides. The front was all sod as was the roof and the remaining portions of the side walls. I don't know the dimensions but one can be quite sure it wasn't very large. I have heard my mother say, however, that it was the warmest house in which she had ever lived. The inside walls were whitewashed.

I have always thought of this house as a dug-out

in the side of a hill to distinguish it from a plain

dug-out used by so many early settlers as their first home.

It was in this house that our mother gave birth to five

children: Grace Olava, May 28, 1890; Rudolf Bernhart, November

19, 1891; Olaf Kristian, December 7, 1893; and Tilda Kristine and

Amanda Bertine, twins, December 24, 1895.

It was in this house that our mother gave birth to five

children: Grace Olava, May 28, 1890; Rudolf Bernhart, November

19, 1891; Olaf Kristian, December 7, 1893; and Tilda Kristine and

Amanda Bertine, twins, December 24, 1895.

On the 20th of September, 1896, Mamma wrote the following letter to her parents and brothers in Norway. This letter was shown to us when we were in Norway in 1970. I have no idea why it was preserved.

It has been so long since we have heard from each other so I must write and send such words as inform to our health. I have longed to write but it has been neglected. First, I must say that we are all well and in good health and I wish that we could hear from you again. Next I must tell you that God in his wisdom has granted us two little girls. They were born on the afternoon before Christmas day so I must say we received a beautiful Christmas gift. They are healthy and playful and were baptised Tilda Kristine and Amanda Bertine. We now have five children and my sister's child as the sixth. Our year was not good as it was a little too dry. Our livestock numbers three cows and two horses.

We have recently had letters from our relatives in Minnesota and they live well and are in good health. They send their greetings and they say they have not heard from Norway for a long time.

I must also send greetings from Uncle Halvor in Iowa (her father's brother). We have had many letters from him recently. He bought land in Iowa and has it paid for and it is worth five thousand dollars. He has been married three times and has a boy ten years old. He says he has written to you but has not received a reply. He wonders if you received his letters.

We have not heard from Gullick Ulberg for a long time.

As I haven't anything else of interest, I must close these simple lines with a sincere greeting to all of you and our hopes that you are in good health.,

Greet Gro from her sister Kristi. Greet those at Myran and Uncle Ole.

Write as soon as possible.

Uncle's address:

Halvor Paulson

Ratna P.O. Winnebago County, Iowa

[ A footnote was added to this letter by Papa: ]

A friendly greeting from me and I ask that you

give a greeting to my old Mother and Brothers at Bjørnsrud.

It seems that it is time that they should write.

Sincerely,

Gregor Bjornstad

Papa's and Mamma's address when this letter was written was: Oacoma, Lyman County, South Dakota.

This was the last year they spent in South Dakota. The following year, in May, they set out for North Dakota and forever said goodbye to South Dakota drought and the horrifying rattlesnakes that scared Mamma so many times as she helped Papa in the hay harvest.

Besides rattlesnakes, they had one other recollection of their days on this homestead. That was a vicious snowstorm that swept across the prairies. Luckily, Papa had shortly before hauled home a load of wood obtained near the river so they kept warm. But their food rations were only a sack of corn and some potatoes. Mamma ground up the corn in her coffee grinder and made up a sort of corn bread so they kept alive on corn bread and potatoes.

The snow was so deep that Papa searched for several days to locate the well. Water was obtained by melting snow. The storm finally eased. This gave Papa the opportunity to get to a store in Chamberlain to obtain other provisions.

The journey north took six weeks. They arrived in Bottineau on July 4th, 1897. They had travelled over four hundred miles in a lumber wagon drawn by a team of horses. With them were six small children, the oldest was seven years of age.

It wasn't an odd decision that they went all the way to Bottineau although Mamma wanted to stop at Leeds in a region that had very good soil about seventy miles south and east of Bottineau. But Papa had a friend in Bottineau by the name of Knut Vikan with whom he had gone to school in Norway and with whom he had been confirmed. Presumably, they had kept in touch with one another and Knut had apparently fallen in love with the Turtle Mountains north of Bottineau and had pictured to Papa that this was the garden spot of North Dakota. The mountains were heavily wooded and hay was plentiful in the meadows. However, in order to develop a grain field, trees had to be cut down, the stumps removed and the rocks cleared away, a job which required time as well as hard, hard labor.

It is my understanding that the Turtle Mountains had not been opened for settlement when our family arrived. However, many quarters had been what they termed "squatted"; that is, settlers had moved on to the land and, thereby, were able to acquire a prior right to title when the land was officially opened for settlement. The quarter that finally became our home had been "squatted" but the man who had the "squatter's rights" decided to leave and our parents took possession. The quarter was about five miles east and five or six miles north of Bottineau, only a few miles from the Canadian border.

The former squatter had constructed a log house and barn. A well had been dug. The house had three rooms. Outwardly, the decision to settle here looked like "a good buy". It was also a community solidly Norwegian and, of course, Lutheran. After the county was organized, our land became a part of what is now Cordelia Township.

Betzy Iverine was the first of our family to be born

on this homestead on October 17, 1898. The following year,

June 18, 1899, Olaf Kristian died and was buried in the old

Vinje Church Cemetery, a short distance from our old home.

Olga Gurine was born on November 8, 1900, followed by Ida Lavine

on January 21, 1903, Olaf Kristian on April 3, 1905, and Iver Leonard

on September 21, 1907. George Adolf was born in Bottineau

on February 12, 1911.

I don't know if it was an old Norwegian custom or tradition that if a son died, the next son born into the family would receive the same name as the one who had passed away. The first son of Papa's father and mother was christened Ole. He died. When the next son was born, he also was christened Ole. I once asked Mamma why I had received the same name as my brother who had died. Her only reply was that that was Papa's wish.

How the family's fortunes developed as the years passed while we lived in the mountains was given to me by Rudolf many years ago.

Once when Rudolf and Gustava returned from California, they visited with us in Minneapolis for a few days. On the evening that they left for Lakota, I also found it necessary to go to Grand Forks. We boarded the same train at about ten o'clock in the evening. The train arrived in Grand Forks at about six the following morning. For eight hours, Rudolf and I sat and talked about those years when he was growing up and I was too young to know or realize what was happening. That night lingered long in my memory.

After several years, Papa got about forty acres of field cleared that could be used for grain. The grain crops were short due principally to the quality of the soil as well as years of insufficient rain. The wheat crop, which was the only grain that could be used for cash income, was limited in acreage and usually was not too productive per acre. Most of the acreage had to be used for livestock feed. Cash income was so low that Mamma finally had to solicit the washing and ironing of laundry in Bottineau. She would pick up the laundry on one trip to town and deliver it the following week.

The crushing economic blow occurred, however, when Papa borrowed money to buy several head of range cattle that were being offered for sale in Bottineau. He purchased them in the fall and his plan was to feed them until they attained a certain weight and then sell them. He had the hay and the pasture to accomplish this end. However, the cattle he purchased were diseased and he didn't know it. The spring following his purchase every animal he had borrowed money to buy was dead. He thus was heavily in debt. He had no cattle. This then presented a real crisis.

How serious a fiscal error this was can only be understood when one considers the cost of borrowing money in those days. Banks then charged fantastic interest rates. I once heard that the usual interest rate was fifteen percent plus an additional bonus of ten percent. How much money Papa borrowed, I do not know. Certain it is, however, that the interest and repayment of principal took every last cent of income the land could produce.

It was at this point that Mamma decided to take the children and move to Bottineau, get a job as a washerwoman and try to support the family.

I don't know the exact year that we moved to Bottineau but the year is unimportant. I have a letter from Amanda stating that she was confirmed in the old Vinje Church, our mountain church home. If her recollection is correct, our move would have taken place about 1909. I know that I was not yet of school age.

I am sure that Mamma's decision to move to Bottineau was a wise one but our parents were not yet free from misfortune. George was born in 1911 and as a result of that childbirth, Mamma spent many weeks in the hospital. The doctor and hospital bills were so large that Papa was unable to meet them. He was threatened with a lawsuit. His only alternative was to sell his homestead. This he did but in doing so he wrote finis to all his hopes for security and status for himself and his family. He was then fifty six or fifty seven years old, far past his prime.

If Rudolf remembered correctly, he received money sufficient to pay off his debts and to make a down payment on a small four room house in Bottineau. Mamma sold this house in 1930 for eight hundred dollars.

After Mamma's recovery, she continued her washerwoman role as breadwinner in Bottineau. Papa found only a few odd jobs. I recall one summer when he worked on the railroad as a section hand and he had a part time job as a janitor in the Lutheran Church. This continued until 1915 when Papa and Mamma decided to take over a restaurant in Omemee, a small town ten miles south of Bottineau. We lived there until 1918 when we moved to Willow City, a nearby town, where we took over the operation of a small hotel. This lasted for about two years when we decided to move back to Bottineau except for another school year in Omemee.

After giving up the hotel in Willow City, Mamma worked as a cook in a hotel in Rolla, North Dakota and later in a hotel in Antler, North Dakota. The four youngest in the family lived with Papa in Omemee the year Mamma was away. This was the year Ida graduated from high school.

In the spring of 1921, Mamma again assumed her role as a laundry maid in the Stone Hotel in Bottineau and the family home was re-established there. In 1924, Mamma rented a twelve room house and set up a rooming and boarding house business. She continued here until 1930, when she sold out and moved to Chicago to live with Amanda.

In the years intervening between 1920, when Papa and Mamma gave up the hotel business, until his death in 1925, Papa's life was not only uneventful but also without any purposeful activity. His hearing had been bad for years and for many years before that he had been troubled by severe headaches. He withdrew completely into himself and spent much of his time reading. In the spring of 1925, he fell victim to a kidney malfunction, his legs and feet became waterlogged to such an extent that he became completely bed-ridden. His doctor advised Mamma that there was nothing that could be done for him.

Finally, on October 29, 1925, it appeared certain that his life was about to end. We had all gathered in his room. Papa asked for a drink of water and I can still see Mamma sitting beside his bed placing teaspoons of water to his lips because he was too weak to drink normally. Shortly, he drew his last breath. Rudolf placed his fingers on his eyelids closing them. He then drew up the bed sheet covering his face.

This ended the life of the young man from Norway who had stepped ashore in Philadelphia in 1874. I am sure he came to America with all the high hopes and great aspirations so common to the immigrants of his day who came to the New World. As with so many, it was not to be.

It was a beautiful fall day as the family followed the hearse carrying Papa's body to its last resting place. The Pastor, in the final rites, chose for his text the ninth verse of the 71st Psalm:

His body lies in the Oak Creek Cemetery in Bottineau. At the head of the lot is a stone simply inscribed with the name: Bjornstad.

In June of 1930, Mamma sold her furniture and her house in Bottineau and, at Amanda's invitation, went to live in Chicago. Mamma wasn't there long, however before she went to work as a maid in a Jewish home on the north side. She continued here until in the fall of 1932, she slipped and fell on an icy street and broke her leg. She spent many weeks in the hospital ward and, of course, didn't return to her job as a maid but went to live with Amanda.

In the summer of 1933, Amanda decided to go to Los Angeles and Mamma returned to North Dakota and lived with George. After George left for California, she went to Rudolf's. Rudolf then lived on a farm near Minnewaukan. I have a letter that she wrote me on May 22, 1935 during this period. It was written in Norwegian:

I must try and write a few words in answer to your letter. I was so glad to hear from you. I wondered why I hadn't heard from you earlier.

I have been bothered with rheumatism the past winter but I feel better now for which I am thankful.

I know you have had a hard time making a living. It seems that everyone around here is living on relief.

Rudolf and his family are well. We have had a great deal of rain and things look good. I hope things will improve.

I haven't anything more to write about. Grace, Olga, George, and Ida are all well and in good health. Bessie is working in a small cafe waiting table.

I must stop with an affectionate greeting and love.

I include this letter because it represents a period when the entire country, and the world, was in the deepest economic depression in history. Mamma, in 1935, was sixty six years old and had been an American citizen since 1887. She had never known a day of prosperity in her adopted country.

It was perhaps this year that Mamma lived with Rudolf and his family that Allen learned to know his grandmother and which inspired him to write the following tribute:

I also remember she made the best pot roast that I have ever tasted.

Grandma had the greatest sense of humor of anyone I have ever known. I don't ever remember her being cross or disagreeable. When she was perturbed or she didn't like something, she would sit at the table in the kitchen and with her left elbow on the table rolling her lower lip between her thumb and forefinger and tapping the fingers of her right hand on the table. I can see her in my mind's eye yet.

In 1959, Dad came back from California in the spring and said Grandma was really old and wanted to see me before she died. We managed somehow to get some money together and went to see her. She was living with Iver. She was still her old self mentally but so old. She passed away shortly afterward.

Yes, Grandma was a grand person. I shall never forget.

From here on, Mamma's spent most of her time with Amanda. Because I worked for a Company headquartered in Los Angeles, I was able to visit her periodically each time I had to report to the Home Office. I could see the ever deteriorating effect of her rheumatic condition. Her hands became knotted and twisted and she began to lose her eyesight and hearing. She told me many times that she prayed that God would grant her release in death.

Iver wrote me a letter which I still have describing those weeks. Following is an edited version of Iver's letter:

I owe you a letter. I am filled with a sort of bitterness and a sense of loss that I can't throw off. I can't think of Mamma without a lump in my throat. Why didn't I do differently in so many ways?

Her passing was surely God's will. But while our actions during her lifetime seemed to be perfectly normal and justified, they don't appear that way anymore. These are the things that bother me.

Mamma's life was hard and rocky and we know she was independent. She was good to us in all her thoughts and actions. When she felt she had been hurt, she always had nothing but forgiveness in return.

When I brought her up here, her eyesight was practically gone and she didn't seem to have a peace of mind. She didn't seem to have the assurance that she had been a good mother.

The first night she was with me, I read her Bible to her and her prayer book. Also, I would read a Psalm and say the Lord's Prayer with her. Her devotion to God and her seeming desire for comfort was so touching that it would tear me to pieces.

The second night she was with us, she asked me, with tears streaming down her face, whether she had been a good mother. She said she lacked so much in ability. Ole, I don't know what happened to me but God must have given me the power and the words that I didn't know I had or could put together. All the good thoughts I ever had in my life seemed to well up within me and overflow in words of assurance and love. We talked until midnight. She finally looked at me and said, "Iver, I believe you are right. I will be able to sleep tonight." She did sleep, Ole, ten hours without waking.

What she really wanted from us kids was not money or Christmas or birthday gifts but an outward expression of our love. That was all she wanted. I tried to give this to her by reading her Bible to her, saying her prayers with her and giving her an affectionate pat on the cheek or gently squeezing her crippled hands and having long talks with her. We talked about incidents that took place when we were kids and in her life. She talked about Rudolf and his hard times and what a good son he had been to her and how good he had been to his family.

God heard her prayers and pleas to take her away. Her favorite Psalms were the 71st and the 23rd. She loved to linger on the 18th verse in the 71st:

Well, Ole, this is the story as well as I can tell it. I hope it doesn't hurt to read this as much as it hurts me to write it.

Iver's letter contains two striking statements. The first: "But while our actions during her lifetime seemed to be perfectly normal and justified, they don't appear that way any more."

This is an interesting observation and experience. Is it possible for one to be the sole judge of his own thoughts and actions? Will a time come in one's life when all his assumed wisdom and understanding of what is true and right in conduct and thought suddenly appears unwise and void of understanding?

The second: "She gave us everything she had and didn't ask or demand anything in return." She was the most unselfish person I have ever known. Surely, in her servanthood, she showed God's strength to this generation and His Power to those who are to come.

I am sure that what I have written about Mamma and Papa in the foregoing doesn't reveal too much about the sort of persons they were, or what kind of home they provided for their children, or what life values they prized above all others. A mere recitation of events as I have given them has little merit in establishing the identity of a person of today with one of yesterday. In the following paragraphs, I am going to try and picture Papa and Mamma as we remember them as individuals.

Papa had a pleasing personality and had many friends. He had the best background in English of any of the Norwegians in the Cordelia settlement, and he was frequently called upon by his neighbors to help them out when they had to communicate with someone in English. In speech, he had a slight Norwegian accent.

He had a good singing voice as a young man and used to lead the church congregation in the singing of hymns. He also was the head of the Cordelia Literary Society. Olga says she remembers one night when he prepared for a Literary Society meeting that he put on a white shirt, a pink and white celluloid collar and Mamma fixed his black tie. She says she thought he looked so handsome.

He also played the flute. Tilda writes that one day at a neighborhood gathering, he and a friend took a boat and rowed out onto a lake. Sitting in the boat, Papa played his flute and everyone thought it was superb. Olga says she remembers him sitting on the doorstep playing "The Last Rose of Summer."

Ida recalls that he paid a great deal of attention to his children when they were small. She liked to lie beside him when he took a nap. One time she was very sick and he took a chair and sat by her bed talking to her. She doesn't recall that he ever punished her. Mamma was the disciplinarian.

He frequently read Lars Linderot's Hus Postille, a book of sermons arranged according to the church year. On days when the family couldn't get to church, devotions were held at home. It was also a "must" that all the children attend parochial school and church services. Confirmation instruction was mandatory.

It was very evident that Papa was not, either by training or temperament a farmer or a pioneer. But he was a victim of his times. There were millions of acres of good land available for the asking. To own land was a status symbol perhaps drilled into him during his formative years in Norway and he thus joined the rest of the land-hungry immigrants westward. However, if he had been fortunate enough to have avoided his one bad business decision and had not Mamma fallen ill, things perhaps would not have turned out as badly as they did in spite of his lack of orientation.

Papa was forty nine years old when I was born. That age differential didn't help me in understanding my father. As I recall, I was at least sixteen years old before I had any talks with him about any subject of any importance. He did, on one occasion attempt to give me a little sex education which, incidentally, I already knew. We talked a little about politics. Now as I look back, he never once told me anything about his father or mother or his brothers or sister and little about Norway. What I knew about his background in Norway, I think, was obtained principally from Mamma.

I did, however, recognize him as a moral man. He never pretended he was something or someone he wasn't. His one outstanding fault was that he seemed to lack confidence in himself and, consequently, failed to show the leadership of which he was capable.

When I think of my parents, however, and the choices they had to make in establishing a home for themselves and their children, how different the challenge and how at variance with the choices their children were privileged to make when they reached maturity.

When Papa and Mamma set out to homestead on the bleak and empty prairies of the Dakotas, they were at the complete mercy of nature. When they built their first sod house, after they had broken up the sod to make a field, and after they had sown the field with seed, there was nothing they could do but wait and pray that God would grant at least harvest enough so they could keep body and soul together. Their only other resource were jack rabbits and wild fowl and whatever fish they could probably catch out of the river. Even when their first five children were born, all they could do was hope that everything would turn out for the best. There were no doctors or nurses or hospitals to whom they could turn for assistance. (Infant mortality in those days exceeded ten percent). This was indeed life in the raw.

I returned to Bottineau in 1973 to attend a reunion of our high school graduating class marking the 50th year since our graduation. A woman, not a member of our class, approached me and told me that the best meal she had ever eaten was one she had when our parents had the restaurant in Omemee. Our high school superintendent once told me that my mother was the most sensible woman in the Parent Teachers Association in Bottineau. There wasn't a business man in town who wouldn't give her credit anytime she asked. There wasn't a man or woman in Bottineau who commanded more respect, regardless of social status, than our mother.

Mamma was the disciplinarian in our house. I can't remember Papa ever laying a hand on me. Mamma, however, believed in discipline and she appeared to have great faith, or so it seemed to me, in a leather strap we had in the house. She used it often.

Mamma was also a very generous person. Tilda writes that when we lived in the mountains, she often prepared coffee and things to eat for the bachelors in the settlement. A frequent recipient of her largess was a man by the name of Knut Strom, also an immigrant from Numedal. In those days of course, no one was ever turned away from the door, even strangers were given food and a place to sleep. "Tramps" as they were called, were numerous.

Mamma was a person of high intelligence. She, also, as Allen wrote in his letter, had her emotions under control no matter what the provocation. I can't remember her screaming or yelling or "telling people off." Our parents never quarreled in the sense that the whole household was disturbed. Mamma was a person with a serenity and humility seldom encountered. In one of Ida's letters to me she said this of Mamma:

The other outstanding attribute of our mother was her utter disregard for things she really didn't need. I never heard her say the words: "I want, I want" and I can't think of any item in our household furnishings or her personal possessions that wasn't useful and practical. She was an expert in knowing what she needed and living within her income. She wasn't interested in "keeping up with the Jones family".

She was intensely interested in any school activity in which any of her children participated. She wasn't always able to go to the football games but she never failed to attend the basketball games which were played in the evening. When the teams played out of town, she called William's Drug Store, the business establishment called by the coach giving the results.

She also could laugh. One time a neighbor lady, French-Canadian by descent and a Roman Catholic who probably couldn't read or write, gave her a lecture on the utter worthlessness of Martin Luther. Mamma laughed for days at this absurdity. We also had a boarder by the name of Billy Patton who had only enough intelligence to stay out of a hospital for the mentally retarded, who after breakfast every morning sat on his chair in the kitchen and told the same story day after day after day. Instead of telling him to shut up, all Mamma did was smile.

Mamma had many friends but the one she seemed to love the most was a woman by the name of Anna Vikan. They kept in close touch with each other and I recall the long telephone conversations in which they often engaged.

Perhaps the finest tribute given to Mamma in the material sent to me was by Allen, which I am going to repeat:

Grace was the first child in our family. Her birthdate was May 28, 1890. Her place of birth was on our parents' first homestead in South Dakota and was seven years old when our parents made that long trip to North Dakota. I have no idea how many years she spent in school but she did learn to read and write. She was confirmed in the Vinje Lutheran Church.

As I write this I begin to realize how little I actually know about Grace. She was fifteen years older than I and was married when I was in the first grade in school. Before her marriage, she was rarely at home as far as I can recall. Then, when we moved to Omemee and Willow City, our contacts became even less frequent.

My earliest recollections of Grace were the times she and Rudolf danced on the living room floor to the music Rudolf rolled out of a mouth organ he held to his mouth. They both loved to dance. I also remember when she was married. Mamma and Papa held some sort of celebration in honor of the newlyweds but I can't recall any of the specifics except, I think, I saw my first bottle of beer at that time.

Grace married Elof A. Moline, a building contractor.

Moline became very well-to-do and perhaps one could call him

rich by the standards of that day. Grace wore expensive fur coats,

she had her own automobile and had what appeared to be an

inexhaustible supply of money. Her house was equipped with the

latest and best in appliances and furniture

and she could set a dinner table with the finest in china,

cut glass, and sterling silver.

In 1920, they adopted a baby boy. He was christened Edward. He was the son of an unwed mother. He, of course, was given every conceivable advantage including a private school secondary education. He died, unfortunately, when he was in his middle forties. He fathered two children. His oldest, a girl, is now probably in her early thirties. The second, a boy, is maybe in his latter teens. Neither of the children, as far as I know has made any attempt to establish contact with our family.

Grace died on July 15, 1940. She, too, was buried in our family plot in Oak Creek Cemetery in Bottineau.

Moline, as we always called him, remarried. He died in 1960.

Although Rudolf was fourteen years older than I, I got to know him better, I think than the other older members of the family. The reason, perhaps, was because we worked together a great deal when he was farming near Bottineau.

The one great feeling of pride I had for Rudolf was when he was called into the military in 1918. I have never forgotten the day he left, March 29. I felt that this was a glorious event in the life of our family. To have a brother, "fighting to make the world safe for democracy," the World War I slogan of the day, was something to be proud of and I was proud. I felt a little "above" other kids in town who didn't have an older brother in the uniform of the country. I followed the course of the war, as reported in the newspaper, with almost a religious devotion.

I also used to brag about Rudolf's life in the Army. Everything I bragged about was the product of my fantasy. One of these was that Rudolf had become a great boxer. I had read about some of the training methods used by the Army to get the "farm boys" in shape. One of these methods had to do with the sport of boxing. I immediately seized upon this and related it to Rudolf. I had every kid in town convinced that Rudolf was one of the very best. One day, after Rudolf's return I brought up this subject of boxing and asked him how good he was at the sport. He turned to me and said, "I have never had a fight in my life."

There wasn't anyone in the family who had less of an opportunity to advance himself than Rudolf. He never had a chance to go to a good school, he wasn't fortunate enough to take over a family farm such as so many in his age class were able to do, to learn a trade wasn't within his grasp, and job opportunities were few and far between for anyone with his experience and background. The only work available to him was farm work for which he was paid, probably, not more than ten dollars a month. When he did go farming on his own on borrowed money at eight percent interest and an agreement to give the landlord half the crop, he actually stepped into a situation that I can only describe as slavery.

Rudolf, however, had intelligence, perseverance, and adaptability. When he could no longer make a living on a farm, he actually taught himself the carpenter trade. It wasn't until he began carpenter work that he started to reap some rewards for his talents and abilities.

Rudolf was a superior individual. He was honest, industrious, and a moral man. No one in the family can take precedence over him as an individual.

Rudolf was a Private in Company E, 137th Infantry, 35th Division. He served in France one year less fourteen days.

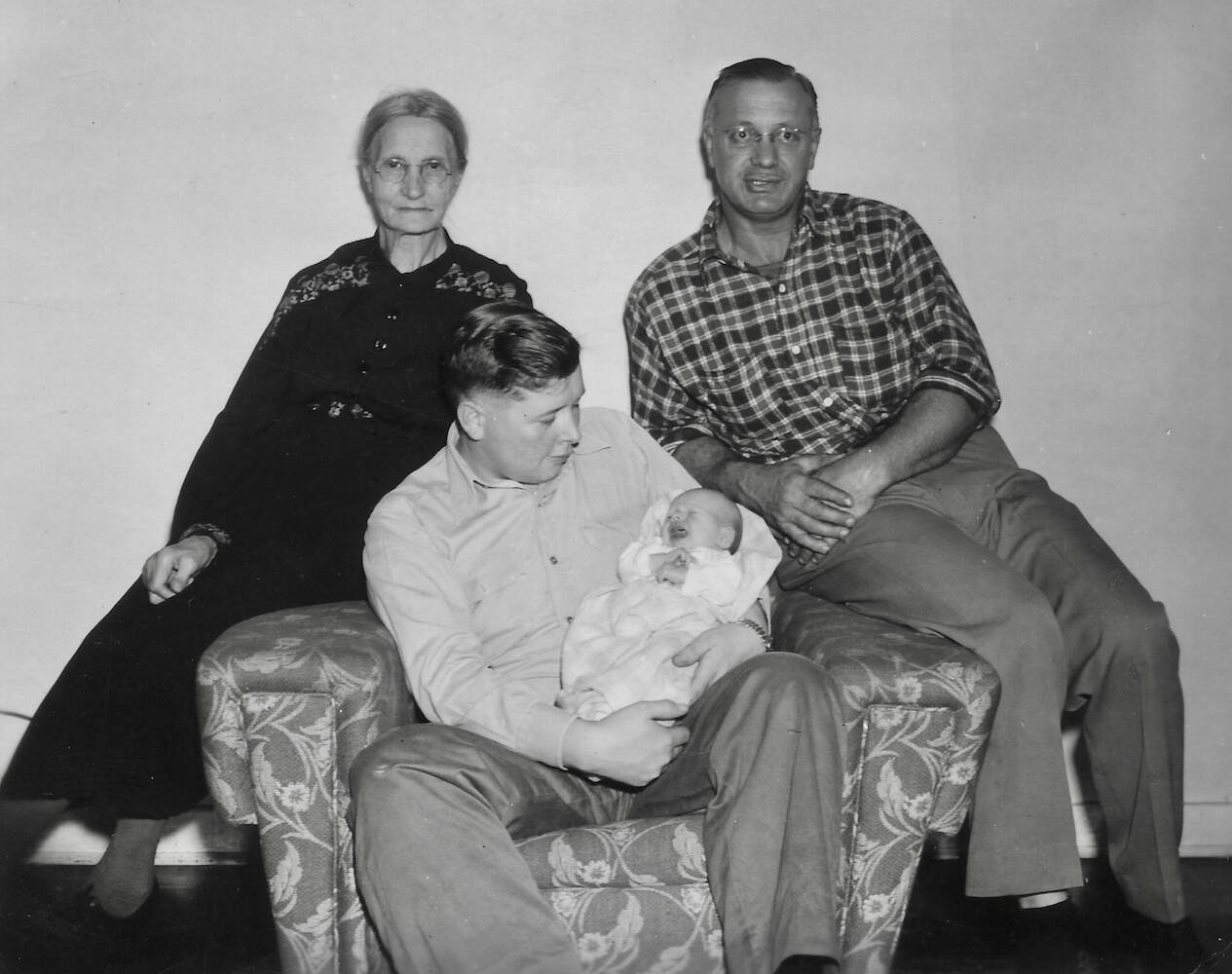

He married Gustava Borgen. They had four children: Gerald, Royce, Allen, and Ann Marie. Gerald, Royce, and Allen have made contributions to this story so facts about them appear elsewhere. Ann Marie, however, forgot to tell me her birthdate. I think, however, that she was born in 1928.

Ann Marie married Richard Barrie. They have three children: Sandra, Russell, and Linda. Russell is now in the Army and is a veteran of eighteen months in Vietnam. Russell recently became a father. A son, Benjamin, was born January 17, 1977.

Rudolf died on February 9, 1963; Gustava on April 29, 1972. Their gravesites are in the cemetery at Lakota, North Dakota.

I am going to combine the material sent me by Amanda and Tilda for the reason that their life as girls and adults were so closely parallel that I would almost have to repeat myself word for word if I were to caption separately.

Tilda and Amanda were two of the children who made the trip from

South to North Dakota with their parents in 1897. At the time,

they were only a year and a half old.

They started to school at age seven. The school they attended was a small one-room country school so common in those years in North Dakota. The teachers in those years had little formal training as teachers and probably had only an eighth grade education themselves. It amazes me when I read their writing that they learned so much under the circumstances.

Tilda states, as does Amanda, that she has happy memories of her childhood in the Turtle Mountains. "We were supposed to be poor people", however, she says that she can never remember going to bed hungry.

We made our own dolls out of rags and our sleds out of apple boxes.

Amanda and I didn't go beyond sixth grade in school. When we were about fifteen, we began to do housework for people in town. Later we enrolled in a Domestic Science course and learned how to sew and cook. After that, our dressmaking careers began. We also took a course in dress making under a Madame Robinson. This gave us prestige and we began sewing for the best families in town. We charged seventy five cents a day.

I will never forget the mountains, especially in June, when the wild flowers were in bloom, the cranes standing in the meadows, the long, long twilights, and the beautiful northern lights that we would see so often.

The day I [Olaf] was born she said that she became very unhappy. She thought the family had enough of kids. When she found out that it was a boy, however, she said she softened. There was an old overcoat which had been hanging in the house for a long time that someone had given us. So she said to Mamma: "Now we can have the overcoat."

Amanda died on the 17th of September, 1976. Her body lies in the beautiful Forest Lawn Cemetery in Los Angeles in the section called Murmuring Trees. She had been in poor health for years.

Betsy, we usually used 's' instead of 'z' in her first name, was born on October 17, 1898, the sixth of our parents' eleven children. She was the first to be born in North Dakota. As I recall she had many friends as a young girl and had a pleasing personality.

She attended high school for two years and then enrolled at an Academy in Willow City in a stenographic course. She worked in local business establishments for a time and then went to Minneapolis where she worked for several years in a large dry goods firm.

In 1924, she went to California. It was when she lived in California that her health began to fail. She developed a severe case of emphysema.

In 1950, she returned to Minneapolis and entered the world famous Mayo Clinic in Rochester. If she received any relief it was not apparent. Shortly before Thanksgiving Day, she suffered a severe stroke and died on Thanksgiving Day in 1950.

Her body lies in the family plot in Oak Creek Cemetery in Bottineau.

Olga was born on November 8, 1890, the seventh of eleven children.

She started grade school while we lived in the mountains and graduated from high school while we were living in Willow City. She ranked high in her class scholastically.

She spent a year in teacher training and continued in this profession until she retired in 1965. During her teaching career she also took additional work at colleges in North Dakota and Wisconsin.

She was married to Leonard Riddle and has one daughter, Betty, and two grandchildren, Steven Weiss and Karla Roth. Steven is unmarried. Leonard died in 1953.

Betty is a graduate of St Olaf College and is a hospital dietician in Green Bay, Wisconsin. She is married to Gene Weiss.

Olga has many pleasant memories of her young childhood years in the Turtle Mountains. She, as well as Tilda, remembers the long twilights, the lonely cries of the coyotes in the stillness of the night, the wild flowers, the Indian trains that would pass our house, and the rabbits playing in the yard in the moonlight.

Vivid in her memories, also, is the family going to church before the services and socializing with friends and neighbors. Church going was more than a purely religious exercise in those days.

Dancing was considered a sin sponsored by the devil. She recalls that Grace once went to a dance and this fact became known to the parochial school teacher. He came to our house and delivered a reprimand so severe that Grace began to cry. He then turned to Mamma and said that Grace's sobbing was evidence of Jesus entering her heart.

Olga's first individual accomplishment was in winning a Biblical Oratorical Contest which was sponsored by the Protestant churches in Bottineau. She was then still in grade school.

Olga has other accomplishments that will always be remembered by other members of the family. No other person has been more generous to her brothers and sisters - not only in terms of money but in terms of service.

Ida was born January 21, 1903. She started grade school in Bottineau but finished her high school years in Omemee in 1921. The following year was spent at Dakota Wesleyan University in Mitchell, South Dakota. Her working years were spent as an office worker in Bottineau, Minneapolis, and Seattle.

Ida has the distinction of having her photograph in a museum in Rugby, North Dakota. Rugby claims to be the geographical center of the North American Continent. Because of the town's unique location, a museum was started there several years ago. A section of this museum is devoted to the legal background of that part of the country. Ida was at one time the secretary to a legal personality by the name of Asmunder Benson. Her photograph is included in the memorabilia accorded Benson.

Ida was married to Charles Oliver in 1931. "Chuck", as we call him, also has Norwegian ancestry. His grandmother died while crossing the Atlantic in an immigrant ship from Norway and was buried at sea.

They have one daughter, Ileana. Ileana is married to Ross Wood and has three children: Tyson, Craig, & Loren.

Ida duplicated Olga's feat in winning the Biblical Oratorical Contest sponsored by the Bottineau Protestant Churches. She read the 27th Psalm.

Ida started painting in 1950 and has achieved more than ordinary success in this art form. She has sold many of her paintings and has the distinction of having one of her works chosen as a part of an exhibition in the Woesner Art Gallery in 1955. We have two of her works on our living room wall.

Ida has a spinning wheel that was given to Mamma by her parents when she departed Norway. It was made by a man by the name of O. Trageton.

Ida has written a trilogy for the benefit of her grandchildren. Rosemaling is now her main interest.

My experiences as a boy and young man were probably duplicated by all of my peers and none of them were of any great significance. Working on a farm in the summer and vacation months, playing baseball, football, and basketball during the school year, interspersed with a little pool, about sums up the total of my activities through my high school years. About the only "dream" I had was to go to Norway – which wasn't realized until 1970.

It it hadn't been for the depression of the thirties, I doubt very much if I would ever have left Bottineau. I was literally forced to leave in 1930 because I had no prospects of finding a job and making a living. Leaving Bottineau was one of the hardest things I have ever experienced.

I went through the usual programs of education which were available to every one of my time in Bottineau. I didn't win any scholastic honors either in grade school, high school, or either of the institutions of higher learning I attended. If I could have exercised any choice in choosing a profession it would have been law. However, "screwing around" as I had to do kept me off balance, so to speak, and finally when I was about twenty seven years old, I thought it was time for me to find something to do that was more stable and had some promise. Even then, stability and promise evaded me until in 1943, I joined the Company from whose employ I retired in 1970.

From as far back as I can remember, I was "nuts" about various forms of athletics. I made the high school baseball team when I was in the eighth grade and when I was fifteen, I played on the Willow City town team as a substitute. I played football in both high school and college. Basketball, however, wasn't my game although I made the squad. I also played a great deal of softball when I lived in Montana.

My most recent love is golf. At one time I wasn't too bad having an eight handicap. One year, I won second place in a Minnesota State Senior Publinx Tournament with a 73.

My only other achievement of note was my winning the state declamation contest at the State Inter-scholastics held at the University of North Dakota in 1923. This gave me a little fleeting fame. I competed against twenty six other contestants from other high schools in the state. I won a gold medal but it was lost somewhere.

I have had a varied work experience. I have worked in the Circulation Departments of three daily newspapers: The Columbus Dispatch in Columbus, Ohio, the Chicago Daily News, and the Spokesman-Review in Spokane, Washington. I have also worked as a salesman for the National Cash Register Co and the Proctor and Gamble Company. I spent the last twenty seven years of my working life with the Occidental Life Insurance Co. of California.

I was married in 1934, April 16, to Alice Thompson. We met in a dance hall in the spring of 1933. We have two sons and four grandchildren. Two of our grandchildren are adopted. They were orphans and Karen and Carsten took them into their home during their stay in India. They are of South Indian descent.

Our oldest son, Carsten, is a graduate of Jamestown College, he has a Masters Degree from the University of Minnesota, is a Licentiate of the Royal School of Music of England and has a Director of Christian Education diploma from St. Paul Concordia College.

Carsten married Karen Brosten in 1963. They have two sons: Kristian Gregor, born April 26, 1967; Harlen Olaf, born April 30, 1969. Their adopted children are: Priya, a girl, February 3, 1972 and Jacob, a boy, born August 15, 1971.

Carsten was born April 20, 1938; Karen January 3, 1942.

Gregory is a graduate of St. Olaf College and Luther Seminary. He is an ordained Lutheran pastor and is now serving a church in Portage, Michigan. He was married but is divorced. They had no children. Gregory was born October 24, 1940.

Alice was born in Mekinock, North Dakota February 2, 1909.

When we were children, Iver contributed a great deal to my physical development. He was always readily available if I felt like kicking the hell out of someone, or if I only wanted to loosen up. This went on until he was about eight years old by which time I had toughened him up to such a point that I reasoned that I had better leave him alone before I got hurt. After that our differences became a simple clash of words.

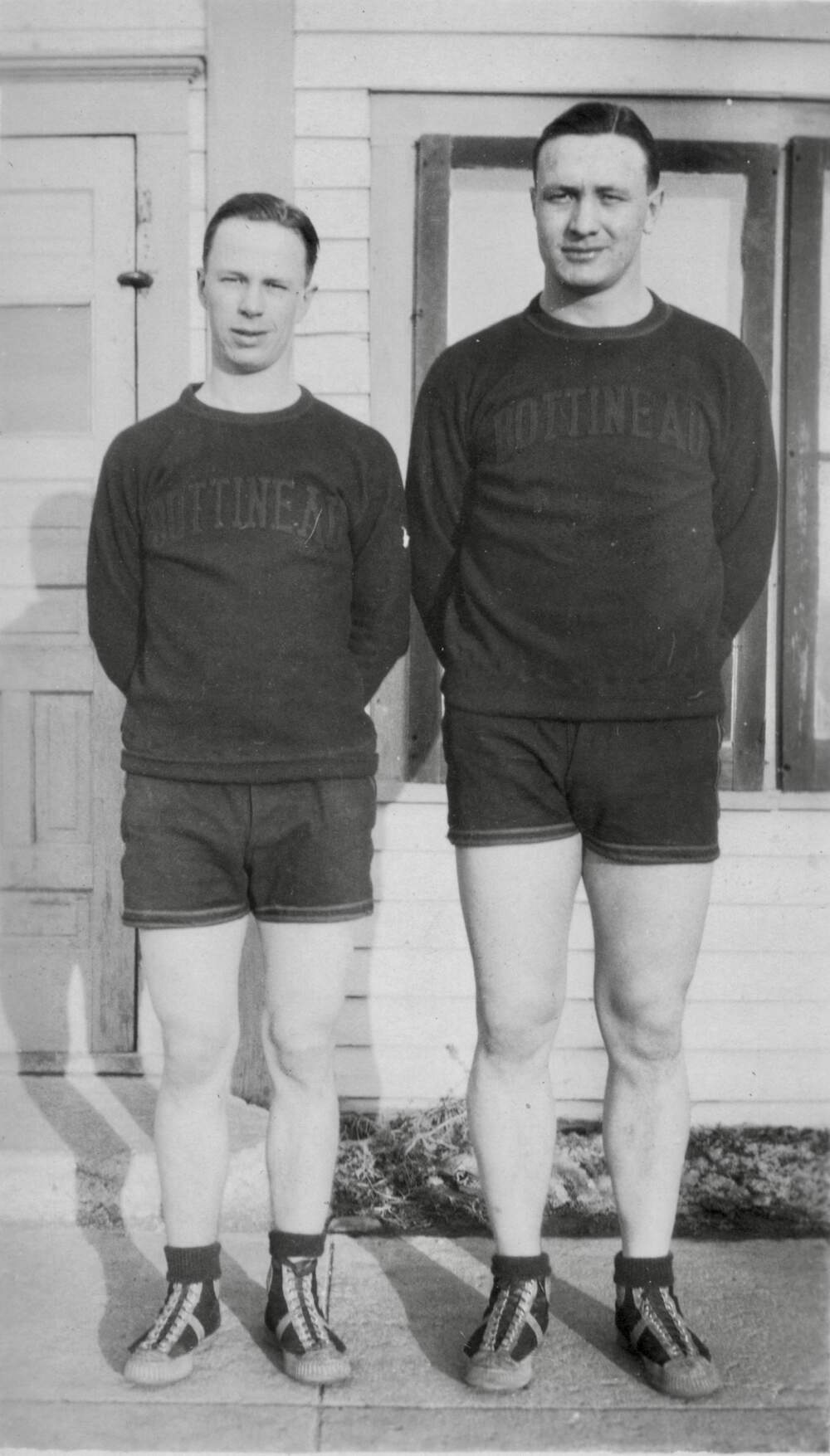

Iver was without doubt the greatest all-around athlete Bottineau High School ever produced. He was also the only Bottineau High athlete to ever distinguish himself in state-wide competition up to 1928 and, I am sure, for many years beyond although I have never checked. He played center on the football team when he was only fifteen years old. He was switched to fullback and proved virtually unstoppable. He played as a guard on the basketball team and won All-District honors.

His major accomplishments, however, were in track and field. He established a record in the shot-put in the State Interscholastics at Fargo in 1928, a record that still may be a record as far as I know.

Iver never did, it seemed, have any great yearning to know what the printed pages between the covers of books had to say. He never did read any of the classics of his day such as "The Rover Boys in College" or Horatio Algers immortal "The Washerwoman's Son". He did, however, exhibit a talent in mathematics in that he could make change properly no matter the denomination of the paper bill. His prime ambition was to discover a gold mine.

He has worked in the oil fields and for many years operated a gasoline and oil service station. When World War II broke out he became a civilian employee of the Navy and was stationed in Pearl Harbor. After the war, he was employed by the Los Angeles Water and Power Company and remained in this employment until his retirement in 1972.

He married Marjorie Munger in 1937. He has an adopted son, Eric.

George was born on Lincoln's Birthday, a national holiday, February 12, 1911.

I remember the day quite well. His birth occurred about midday.

Of all the people I have ever known, I have never met anyone so "crazy" about athletic competition as George. He played center on the high school football team as a freshman, the first of his four years on the team, weighing only about one hundred and fifteen pounds. He played guard on the high school basketball team for four years and to witness the intensity with which he played, one could assume the game was for the world championship.

His crowning athletic achievement was his designation on the All-District team as a guard in 1928. In that year, the Bottineau team lost the district championship by one point. That 1928 team was so highly favored to win and go to the State Tournament that every daily newspaper in the state had prepared a headline announcing the winner as Bottineau. That game was indeed an "upset".

After his graduation from high school, he attended Jamestown College

for two years before moving to California. He retired in 1977 from

the employ of the Newhall Public Schools. Since his retirement, he tells

me he has learned to shoot a revolver and works part-time as a Security Guard

– looking for robbers and burglars. To date, he has managed

to avoid them.

George was married to Myrtle Engen. They have two sons: George Owen. and Barry and six grandchildren.

Gerald was born in August 8, 1920 at Willow City, North Dakota. He was the family's first grandchild, the son of Rudolf and Gustava.

Gerald spent all of his pre-teenage years on the farm. He was terribly afraid of roosters and when he was still hardly out of diapers, he found a pistol and planned a massacre. His Mother foiled the plot and took the pistol away from him.

Another of his fond memories of his childhood was a hired girl they had on the farm one fall who chewed tobacco. She wouldn't admit to this habit but every so often she would lift the lid on the cook stove and spit into the fire. His parents assumed the old lady had bleeding gums and that she was spitting blood. He states, however, that it was tobacco. He doesn't reveal how he was so certain that it was tobacco; however, maybe the old lady liked to take him in her arms and fondle and kiss him. Gerald at that time was only about five years old. He has never used tobacco.

Of those years on the farm, he recalls the times his father's younger brothers would come out to help his father during the haying and harvest seasons. One of the more than insane escapades he observed in the life of his uncles was when I always grabbed a bar of soap and a towel and ran out behind the barn when it rained and showered. I tried to tell him that that was the way Adam did it after he was kicked out of the Garden. But he still thinks I was a little off center in the head.

Gerald also remembers the collapse of the farm market in '29 and '30 and the hordes of grasshoppers that moved in on the grain fields in those years destroying every last shred of standing grain. His most memorable day as a youngster was one morning he walked to school in 53 degree below zero weather.

Gerald attended three different high schools: Devils Lake, Minnewaukan, and Lakota. He graduated from the latter school.

In 1941, he went to California and started work in the Lockheed Aircraft Plant. In 1942, he married Agnes Olsen, a girl from his hometown of Lakota, on April 17, 1942. In November of that year, he entered the Army.

He spent three years in the military a part of which was spent overseas in the Pacific. He was a member of the Air Force and his unit was awarded the Presidential Citation. He was returned to civilian life in 1945 and became an apprentice carpenter. He has followed this occupation since.

He and Agnes have four children: Gayland, born April 26, 1943; Karla, born June 2, 1949; Rolf, born July 5, 1952; and Owen, born May 19, 1956.

Gayland also served in the Army. His term of service was with the occupation forces in Germany. While in Europe, he met and married a girl from Stavanger, Norway, Ase Naeland. They have one child, Bjorn Gerald, born October 25, 1975. Of interest is that Bjorn represents the fifth generation in America bearing the name Bjornstad.

Karla's married name is Tschetter. She has two sons: Jonathan, born November 14, 1969 and Michael, born November 29, 1971.

Rolf married Elizabeth Berg, May 10, 1975. Rolf is in his third year at Luther Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota studying for the pastorate in the American Lutheran Church.

Royce was born in Bottineau, North Dakota on September 9, 1921, the second son of Rudolf and Gustava.

Royce followed the usual childhood and school patterns of his day and in 1940, on September 18, he enlisted in the United States Navy. He went through recruit training at the Great Lakes Training Station in Illinois and on February 14, 1941, he graduated from the Hospitalization Corps School in San Diego, California. After a short tour of duty at Mare Island, he was ordered to the M.S. Naval Hospital, Caracas, Cavite in the Phillippines Islands. He arrived there on September 25, 1941, only a few weeks before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

On the second of February, 1942, his unit was taken captive by the Japanese and he found himself in Bilibid Prison in Manila. He was later sent to Japan under the guise of setting up a hospital in Kobe. Instead, he arrived in Osaka and was put to work in a steel mill.

On March 14, 1945, the Americans fire bombed Osaka and in doing so hit two barracks in his camp. He was then transferred to the northwestern coast of Japan to Nautsu where he was again put to work in a steel mill.

By this time he was in very bad physical shape and suffering from Beri-Beri. He was so filled up with body fluid that he weighed two hundred and twenty five pounds. Luckily, his kidneys started to function again and by August 14, 1945, he was down to one hundred and twenty two pounds.

He was liberated in Yokohama on September 5, 1945.

Royce remained on active duty in the Navy retiring as a Chief Hospital Corpsman on June 10, 1960. Since his retirement, he has built up a lucrative insurance business in Sunnyvale, California.

He married Ruth Olson on November 18, 1945. They have two children: Pamela, born November 12, 1947 and Roger Bruce, born February 16, 1957.

Allen, the third son of Rudolph and Gustava, was born in Bottineau, North Dakota on August 13, 1922. He was probably the tiniest Bjornstad ever ushered into this world weighing only two pounds and ten ounces. I can recall that Mamma was amazed at the size of the baby.

His first six years in school were spent in a one room rural school near Bottineau. He attended the Minnewaukan schools in his seventh and eighth years. His high school years were spent at Lakota High School from which he was graduated in 1940.

Allen has an extensive education beyond high school. He is a graduate of the University of North Dakota with a B.S. in Education, a Master's Degree, also from the University of North Dakota and has pursued post graduate studies at San Jose State, Arizona State University and Santa Clara University. His studies were in the fields of Education, Chemistry, Mathematics, and the Natural Sciences. He is now the head of the Science Department at Wilcox High School in Santa Clara, California.

Allen's education was interrupted by service in the military in World War II. He enlisted in the Navy on October 16, 1942. He was trained as a turret gunner in the Air Force and served on a Torpedo Bomber. All of his combat duty took place in the Pacific ranging from the Majuro Atoll to Guadalcanal, New Guinea, and finally Japan. He flew in the Victory Air Parade over Japan at the signing of the peace treaty. He was discharged from the service on December 23, 1945.

While in the service he received the Air Medal, the Presidential Citation, and four stars on the Asiatic-Pacific campaign ribbon. He left the Navy as a 1st Class Aviation Ordinance man.

Allen married Yona Thorleifson on January 21, 1945. Yona's date of birth was December 19, 1923. She is also a graduate of the University of North Dakota and has taught school for many years.

Yona and Allen have three children and two grandchildren.

Elin Olivia, their daughter, was born December 8, 1947. She is married to Joseph Allen Ovick. Joseph was born on December 19, 1947. They have two children: Joseph Bjorn, born January 4, 1974 and Jon Michael, born September 10, 1977.

Their first son, Jon Gregor, was born on October 20, 1949. He won many honors in mathematics in his years at the University of California and was awarded a fellowship at the University of Maryland. He once worked with the United States Census Bureau but recently resigned and is entering the field of nutrition.

Leif Bernhardt was born on August 14, 1953. He is a research chemist.

This saga is being written with the thought in mind that others may add to it if such is their wish. All I have tried to do is to record the highlights of the material sent me. Thus, the preparation of these pages should not mark the end of the Bjornstad story. Actually, it should be only the beginning.

We were a large family. Every family, I suppose

develops certain manners and traits. Possibly, the one outstanding

characteristic of the children in our family was that each one

of us seemed to have the idea that he was the only one to whom God,

in His providence, had given special insights to truth and reality.

Therefore, the words each spoke took on the nature of absolute verity.

One can imagine the state of affairs when two of the family seers

arrived at opposing positions in an argument. (We never had discussions.)

I am sure that even God put cotton in his ears to shut out the noise.

I recall some of the profound judgements that were applied to me. I was lazy, dishonest, an educated fool, and surely headed for the penitentiary. Of course, I, too, prophesied about other members of the family; probably in more detail and certainly in a louder voice. I know I did a masterful job at times.

In closing an argument, we never embraced or hugged our opposition. Instead, we screamed at the other person the following words and usually in unison – "You're a damn fool."

Also, the words "darling" or "dear" were never used in communicating with a brother or sister. In verbal situations, we always used more descriptive terms. To us "darling" of "dear" sounded so "gushy" and made the speaker appear less independent and strong. We all wanted a robust, vigorous, and powerful profile to present to our fellow seers.

Another word entirely foreign to our speaking vocabulary was the term "honey". We couldn't relate the same of such a delicious substance to the person of a brother or sister. We all reasoned, and I believe correctly, that there was no more sense in the word "honey" than in such words as "molasses", "vinegar", or "syrup." However, the word "pig" received complete acceptance in direct address.

In a more serious vein, I never felt in my grade school or high school years that I was "under privileged" or "culturally deprived". I never had a teacher who in any way neglected me either in the interest shown in my progress or in choosing me for participation in such things as a class play or other type of school program. One of the nice things, of course, in our time was that few families had more than they needed and knee-jerk "liberals" had not yet come out from behind the woodwork. Also the era of "Big Think" had not yet arrived.

One of the satisfactions I have encountered in writing this story is in trying to present facts in their true light. Every thing I have said about my parents and brothers and sisters I believe to be true. However, we children did not comprise a Society of Saints. We quarreled, we argued, and we sometimes used words that I can only describe as the underside of language.

Throughout our life together, however, I always had a feeling of belonging and that there wasn't a member of our family who, if a brother or sister had asked for a loaf of bread, would have turned his head.

Of those who now live only in our memories, Papa and Mamma, Grace and Moline and Edward, Rudolf and Gustava, Leonard, Amanda, Betzy, and the brother who many of us never knew, the following lines come to mind:

Grace Olava was born May 28, 1890 on our parents' homestead in South Dakota. She loved to dance and when we lived in the Turtle Mountains the young folks would meet in their houses and dance.

Grace had a beautiful black fur muff. Grace had a boyfriend named George Gunderson who always walked he home from the dances and parties. At one time Rudolf told Mama that George and Grace walked along with their hands in the muff. He thought this was sinful.

She left school at an early age and went to Bottineau and worked as a hired girl. Now they are called maids. She gave Mama a portion of her money to by food and clothing for the little kids in the family. She was very generous with her money. When we were confirmed she gave us a ring. Mine was a birthstone ring which had a topaz setting.

When I graduated from high school I won a scholarship of $100 to a secretary school in Fargo. I did not have any money to attend this school so Grace said "come and live with me and you can go to the school of Forestry for one year." This I readily accepted and that started me on my teaching career.

Rudolf Bernard was born November 17, 1891 and died February 9, 1963. He left school at an early age and worked as a hired man on the farms in the area. He, like Grace, also gave Mama some money to help her to buy food and clothing for the family.

Rudolf and Grace liked to dance and they went to all the neighboring dances. Rudolf played the mouth organ and was the caller when they danced a square dance.

I remember one time when we lived in the mountains that I had to go to the toilet. It was evening and Rudolf was told to take me to the back house which was a short distance from the house. He didn't want to take me but Mama made him. We ran all the way. That evening the northern lights were very bright. Rudolf didn't stop to admire their beauty and said "We have to hurry and get into the house because when the northern lights are so bright that means the world will soon come to an end." Also, that if I urinate and have bowel movement at the same time, meant that I had inflammation of the bowels and that I would die. I was very scared and sure that I would die.

Rudolf was called into the military service in World War I. We lived in Omemee then and the town gave a party for all those young boys who were drafted. I was very proud to see him on the stage where he was presented with a ring. He wore it all through the war.

The boys met in Bottineau (the County seat) and boarded the train there. The train stopped at every town, the band played, and everyone called "Good-Bye". Rudolf sat by a window and he held out his hand to me and Ida. We hung on and cried until the train moved. One lady came up to us and said, "This is no way to send your brother off to war." We did not have school that day so some of the girls went to the Domestic Science room and made fudge.

Rudolf served in Comp. E, 13th infantry, 35th division. He served in France one year and 14 days. This was the war to be fought to make the "World safe for Democracy." In those days was was fought in trenches. He told me that one day a group of the men were sent on a reconnoiter mission "to see what they could see." At one point they looked over the top of the trench and saw a group of Germans. They turned and ran back to camp on a dead run!

On his return we lived in Willow City where my folks ran a hotel and restaurant. George was then about six years old. He ran to the neighbors, knocked on the door, and shouted "My brother is home," and then ran on to the next neighbor and so on. One of the songs we sang during the war ran like this:

Rudolf sent a pink silk handkerchief trimmed with white lace to me (Olga) from France. In one corner was embroidered a U.S. Flag and a Fleur-de-Lis flower witht he word "A kiss from France". I still have it put away in a box with my other keepsakes.

Now when I recall these events I realize that the younger children did not appreciate all that Rudolf and Grace had given of their time, energy and love so that we could be more comfortable. Read the Book of Esther in the Bible and you will see what I mean. It shows that every day we have the opportunity to give a piece of ourselves so that another person might live more completely.

The seventh child of the family was "Me", Olga Gurine. I was born November 8, 1900 in Cordelia Township in the Turtle Mountains of North Dakota.

When my Great Grandson, Erik Roth, came to visit us in the summertime he liked to hear me tell of the time when I was a little girl. I have written them down and they are in an album because Betty decided that she wouldlike to have this down. I will not repeat what happened except that my childhood was a happy time and I have fond memories.

I finished grade school in Bottineau. When I was in the seventh grade the family moved to Omemee where they ran a restaurant. I stayed with Amanda and Tilda to finish the year. Before school was out my friends gave me a surprise farewell party. They gave me a fingernail file as a farewell present. I still have it in my box of "Memories". But in the fall Mama decided that I was of Confirmation age and I was sent back to Bottineau.

I stayed with Grace until they decided to go to Minneapolis to spend the winter. Mama found me a place to work for my room and board in the home of one of Grace's friends. The man was a lawyer and their names were Erik and Ida Moum. I was small for my age but the lady decided that I needed a corset and she bought me one. I didn't like to wear it but it pleased her because it kept me warm and I needed it since I had to walk about a mile to school I attended two years of high school in Omemee and two years in Willow City where my folks had a hotel. Ida and I helped our parents with the work. We had about 12 steady room and boarders who worked on the building of the Catholic church. After my high school years I attended one year at the School of Forestry in Bottineau. Grace paid for all the expenses.

My first year of teaching was in a two room school at Kuroki, a "train stop" between Antler and Westhope. The other teacher was Prestoria Ogg and she lived with her parents in Antler. I got a room at the hotel where I also ate my meals. We took the train at 7:30 in the morning and went back at 5 pm in the evening. Our fare was 20 cents each way.

My first year of teaching was not a success. I was lonely and Prestoria was not a very friendly person. The town had no entertainment except dances every Friday evening at the town hall. This was fun because I did like to dance.

I had to earn some credits to keep my teaching certificate valid so I went to Valley City, where I had friends and attended the summer session there.