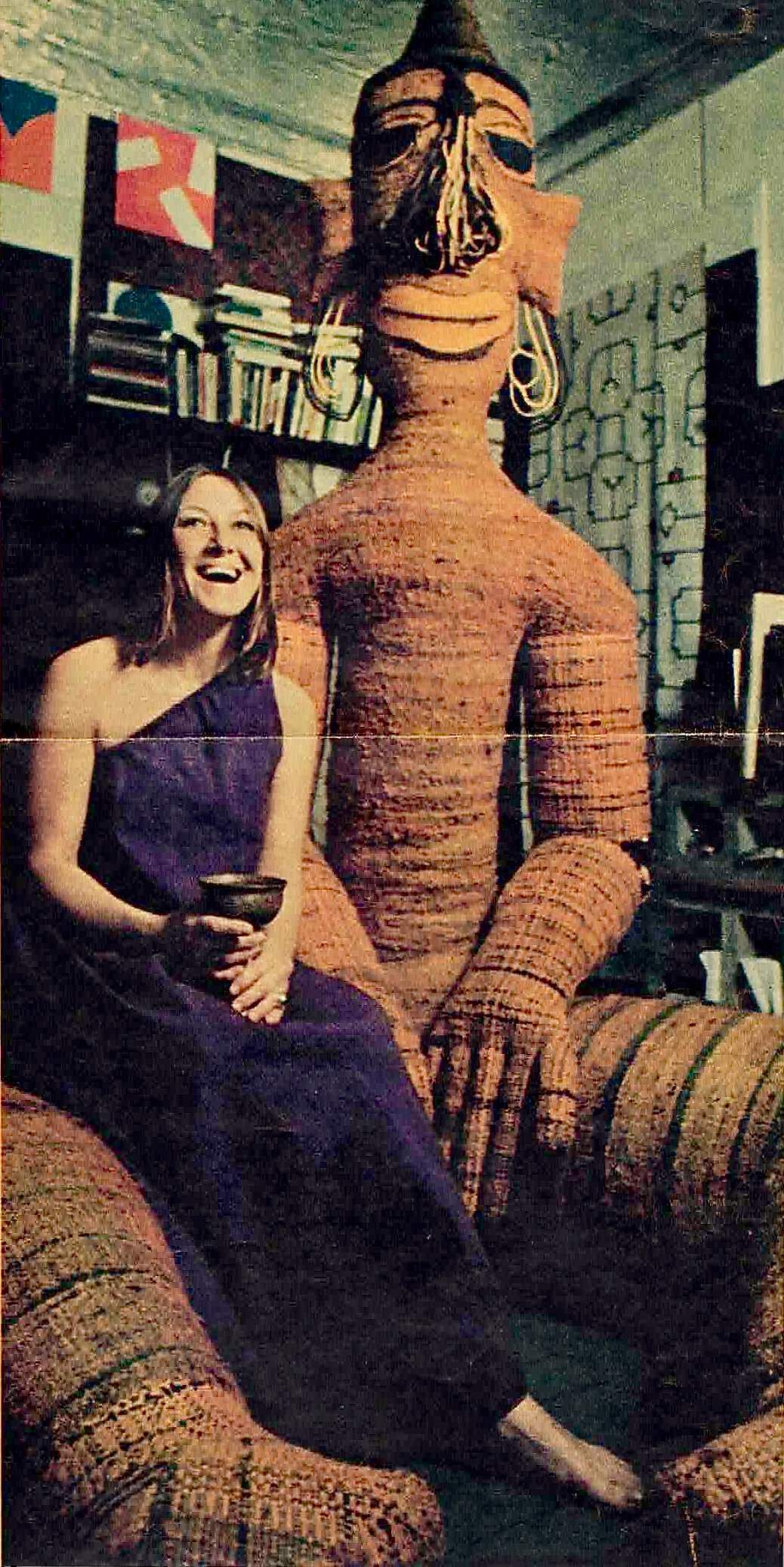

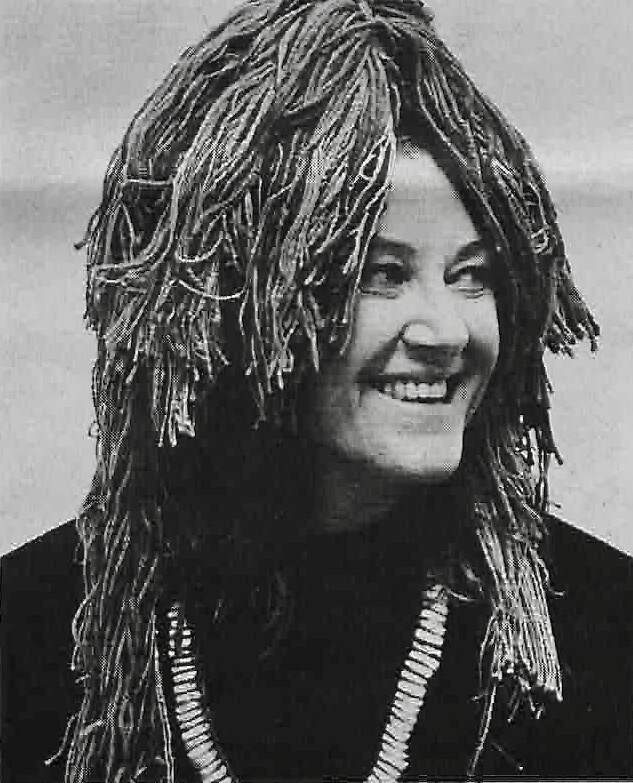

There is a weaver who lives in Lagunitas in a hillside cabin with a Red Indian Woman and a Yellow Buddha. The buddha sits on the floor of the living room and is 7 feet high in that position. Visitors to the cabin sit on the buddha's thighs. It's comfortable, stuffed with kapok, and a wonderful place to park while you're talking about Tibetan mysticism with Barbara Shawcroft.

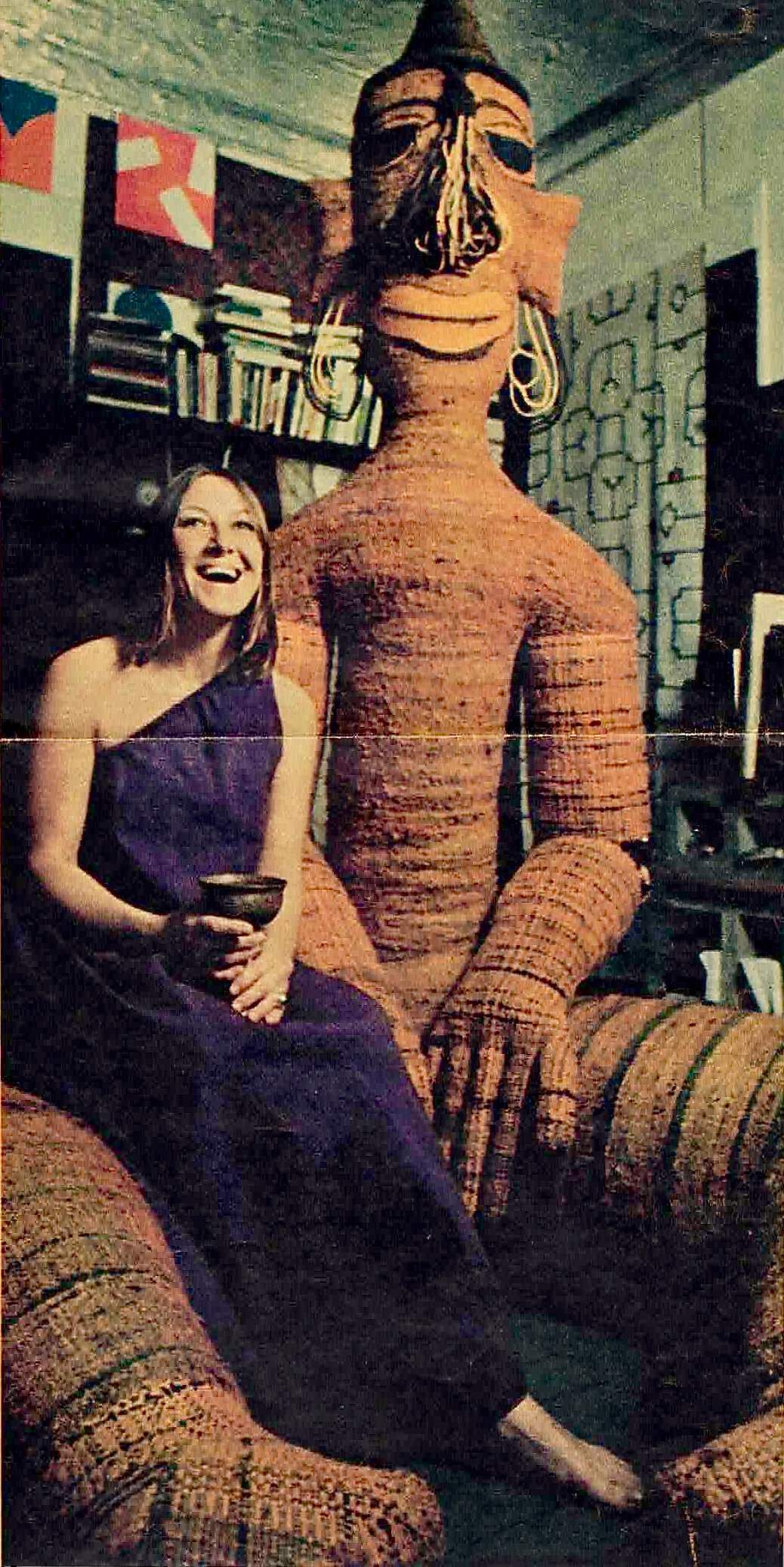

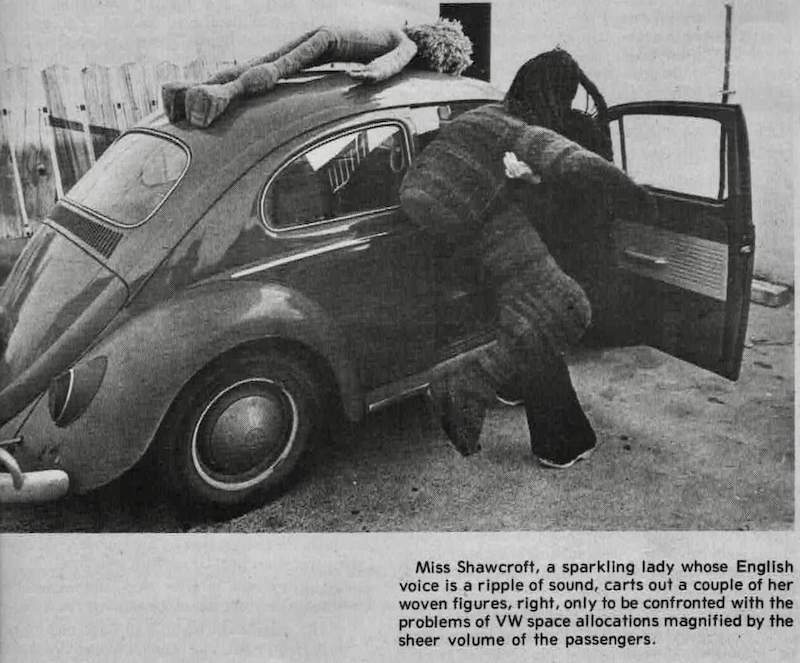

Barbara, the wife of architect Richard Kamler, weaves

three-dimensional figures – huge figures, larger than life,

like a nine-foot Black Man, an eight-foot-high White Woman

and a Green Child that tops five feet. The color of the child

figure symbolizes growth and hope, says Barbara.

They'll all be on display Nov 4-29 at Anneberg Gallery, 2721 Hyde St. in an exhibition called "The First World of the First People: A Woven Environment."

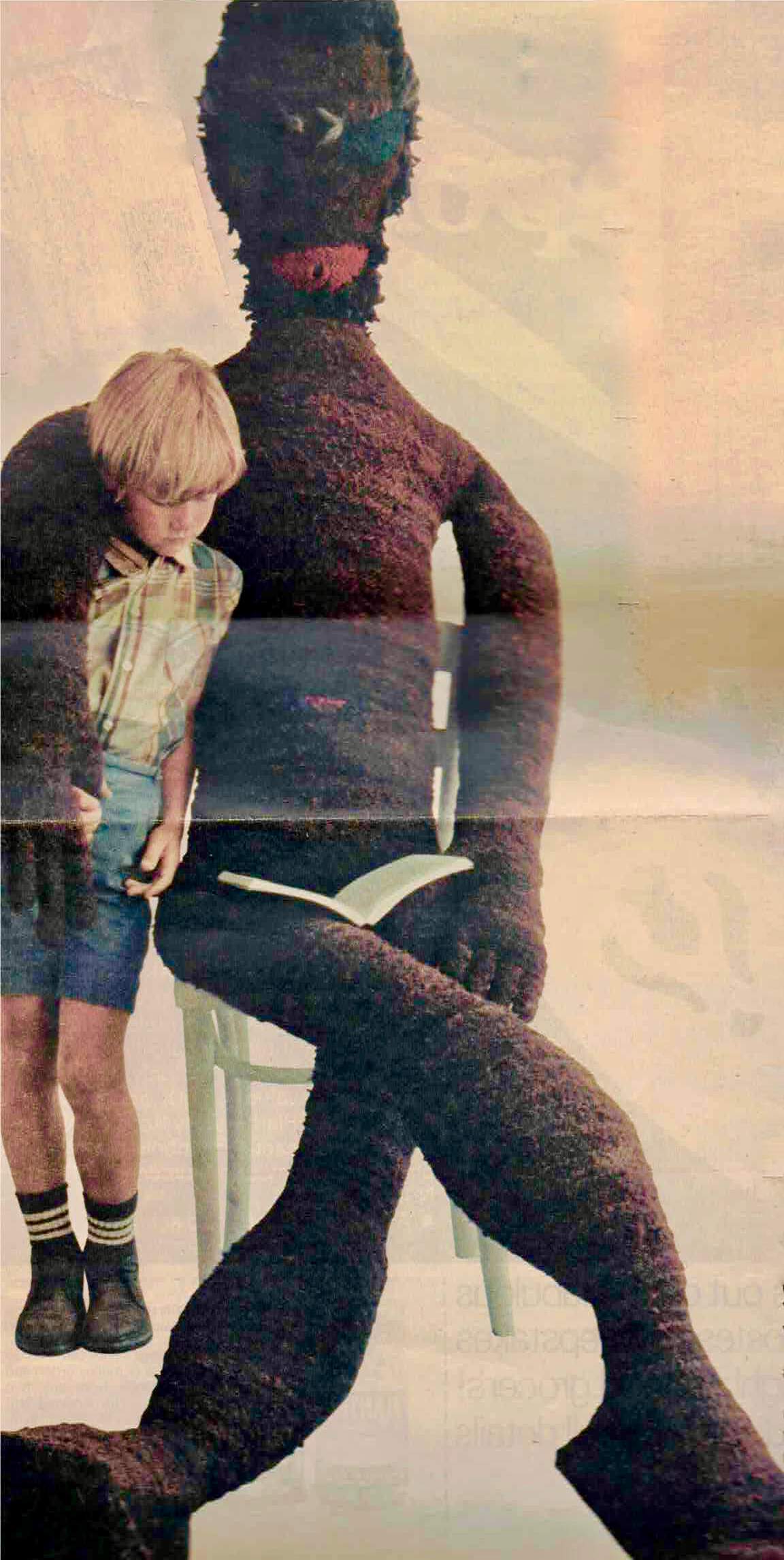

But let's not stray too far from sitting on thigh of Yellow Buddha with Sapphire Eyes and talking to Barbara. It's fun. She talks about her art form, about philosophy and about Tibet. Sometimes, while talking about Tibet, she wears a woven mask or wild wig of yarn.

"I'm dying to go there," she says, "it's so groovy. I have the feeling that I'm from there; that to go there would be going home. Somewhere in Tibet is the secret of life. Perhaps it's written on the wall of a cave in some unknown language. Wouldn't you like to go there and find it?"

You sit on thigh of Yellow Buddha, glance at brooding figure of Red Indian Woman who is staring you down and say, "Ah...hmmmmmmm. Is there any more of this clever German wine?"

Barbara fills your cup (hand-moulded ceramic, naturally) and goes on: "I've woven a Tibetan mantra*, too. See?"

You look inside the woven vessel and read the words inscribed on the bottom: "OM MANI PADME HUM." In case you've forgotten your Sanskrit, that translates roughly as "hail to the jewel in the heard of the lotus."

* The mantra, a series of sacred syllables, is intoned by Tibetans and Hindus. The mantra syllable "HUM" of the Tibetans and the "OM" of the Hindus is said to be the most effective, and is associated with the psychic centers of the lower part of the body, according to "The Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation." - Oxford University Press

"Not everyone has one," you smile admiringly. "And how did you get into this people-making business?" (The business of interviewing always gets in the way of delightful afternoons.)

Barbara pauses and looks out of the geometric design covering her window, looks out on a patch of filtered sunlight brushing a deep green hillside. "It's something special, you know, when you have a small space to look out at something beautiful."

Her face lights up, then darkens. "I was born in England, in Essex, and moved to Toronto. I had studied painting and pottery making, but I was still searching for my own thing. I started to weave and I liked it."

"I apprenticed myself to a weaver in New York – Lili Blumenau – for a year, and later worked as a weaver in the Jack Lenor Larsen Gallery on West 59th Street. Weaving started to grow on me. I won a summer scholarship to the Haystack Mountain School in Deer Isle, Maine."

All of this time in New York and later in Montana and in San Blas, Mexico where she lived for a year, the idea of weaving something big was taking shape in the back of her mind.

"Then, three years ago, I knew I wanted to weave people," she says,

"not only people, but an environment with people so big you

could get inside of them, live with them."

Working often 16 hours a day she completed Black Man, White Woman and Green Child during 1967. Her latest work, Yellow Buddha with Sapphire Eyes took six months. It has $200 in raw materials, 12 pounds of yarn and is stuffed with 70 pounds of kapok. The head and torso were woven separately, the legs in three sections. This was an innovation. Her first figures were woven in one piece.

And how do you weave a nine-foot-high figure in one piece? "I make rough sketches. Never make a model, just visualize the whole figure in my head and begin to weave."

Barbara works out the proportion as she goes along and says, "It grows and changes as I weave and even the original impression will change. It's a visual thing."

Thus she constructs Buddha and Indian women on her French-Canadian loom that is a simple, functional design more than 100 years old.

"Over there," you point with your empty ceramic wine cup at a tent-like structure in the corner of the living room, "what's that?"

"It's a meditation or love space. The base is six feet in diameter and it's about seven feet high big enough to get inside of. I have plans for it ... a growing space with rooms and woven people in it and a jungle outside. There are some of the vines," she says and nods toward the ceiling.

You look, and sure enough: There are some green feathered vines hanging down from the ceiling.

"I got the idea for the foliage in Mexico," she says. "Have you ever seen the sky in San Blas? It has a green glow. It's primitive; the first environment."

"I see," you say, even though you don't. "And what's that hanging thing over there?" It appears to be in the shape of a cone, alive-looking with strands of yarn dripping from the sides.

"It's a lump," she says, "part of the jungle environment. It seems to be taking on a floral shape. Do you like it?"

"Ah...hmmmmmm. Tell me some more about Tibet."

Barbara's ever-changing face skips on to a new expression. "Here, read this," she says and hands you a book.

You read: "The meaning of the mantra consists in its multi-dimensionality, its capacity to be valid not on one, but on all planes of reality and to reveal on each of these planes a new meaning – until, after having repeatedly come through the various stages of experience, we are able to grasp the totality of the mantric experience-body."

Says Barbara: "This explains my work and my life. My work is my life." In another book in her own handwriting she has noted that "form and movement is the essence of environment, these being the secret of life and the key to immortality. Transformation of form is life itself."

"Do you understand some of this," she asks her visitor brightly.

"I'll try," you say. "If there's any more wine left, if you fill my cup and let me wear your Tibetan hat for awhile, it will be easier." She does.

Later, driving back to the office, you think about the afternoon in the company of huge woven people and a philosopher-artist, and the thought takes shape:

"How in the name of the great Tibetan mantra do you put this

groovy experience down on paper?"

To the Index