Ten years ago, Ward Maillard never dreamed he'd sell his Sonoma County restaurant-night spot, move within a stone's throw of Gilroy and work for free.

But that's exactly what happened.

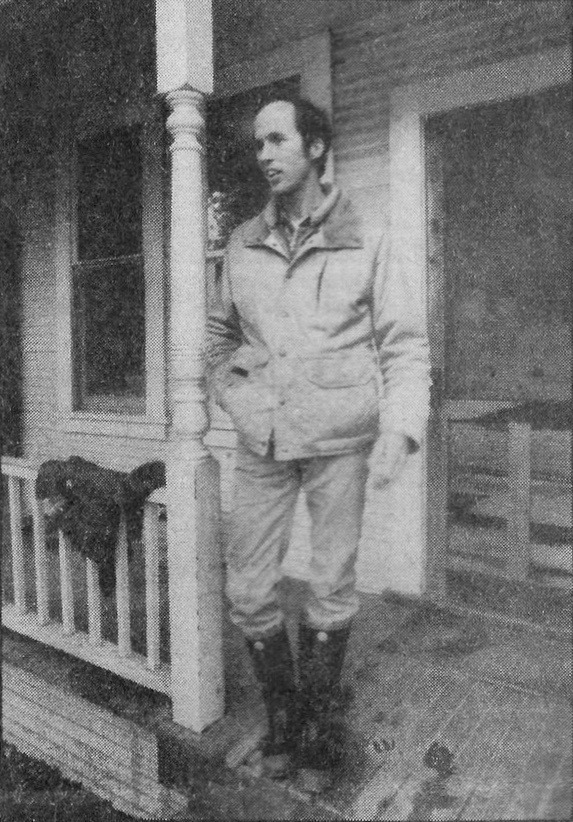

The bright good-looking 36 year-old now goes by Sadanand (Sanskrit for “ever happy”) and handles public relations for Mt. Madonna Center for the Creative Arts and Sciences - a yoga retreat center he helped found six years ago.

Located on Summit Road, just over the line into Santa Cruz County, the center is only 15 miles from Gilroy.

In this scenic spot, overlooking the entire Monterey Bay, Maillard now practices yoga two hours a day and studies the teachings of master yogi Baba Hari Dass.

He still describes himself as a skeptic who is not taken in by robed swamis who preach brotherhood to fatten their pocketbooks.

It all started back in Sonoma County when Maillard tried yoga as a way to relax from the constant strain of the restaurant-entertainment business. About that time, his bank manager introduced him to an Indian teacher who had no income and no church.

After several years study with Babaji, the term of affection and respect by which the teacher is known to students and friends, Maillard decided the robed, bearded spiritual leader was “100 percent legitimate.”

He describes the teacher as “independent of his culture” and different from “other Indian teachers who set themselves up at the center.”

“Basically, if he's teaching anything, it's to stand on your own feet and make your own decisions,” Maillard says.

Yoga is not a religion, he hastens to explain. Like prayer or meditation, it's a tool for people seeking peace of mind - whether they belong to a church or not.

Within a few years, Hari Dass had dozens of followers who formed the Hanuman Fellowship and held retreats throughout the Santa Cruz area on yoga - the ancient Indian meditation practice which, Maillard says, helps a person lose his sense of ego identification and develop an ability to concentrate. Maillard is now president of the non-profit fellowship.

In 1976, 40 fellowship members donated $1,000 each for a down payment on a 360-acre permanent retreat spot on top of Mt. Madonna.

They could hardly have found a more beautiful spot. On a clear night, staff members can see the lights of Santa Cruz, Watsonville, Salinas, Monterey, and Carmel.

To learn more about the center, get up early some Saturday and take the pleasant drive up Hecker Pass. Free yoga lessons go from 7:30 to 9:30 a.m., and a $2.50 breakfast is served at 10:00. You don't have to be svelte and limber to participate.

Last Saturday's menu included a rice cereal spiced with coriander and cumin, fruit salad, unflavored yogurt, homemade bread rolls and spiced Indian tea.

Some 200 people, including 125 participants in a four-day Easter yoga retreat, ate on the floor. Rolls of paper were spread on the carpet as tables.

People wanted to be near him, even though he never talks. A staff member said the 61-year old yogi took a vow of silence 30 years ago. When someone asks him a question, he pulls a book-size chalk board from his pocket and writes an answer.

“How should a person deal with loneliness and fear?”

“Fear, fight, finish,” he scratched on his board.

When asked to elaborate, he wrote, “If you're afraid of a ghost outside, you can sit inside and imagine and scare yourself to death. If you go outside and face the ghost, you'll see there isn't one and the case is finished.”

When asked whether eastern spiritual practices benefit westerners, he replied “There is no difference, only the difference of language.”

When asked about the value of not talking, he wrote, “Can't fight. Also it is one of the ways of preserving energy.”

The center, which is run by a 10-person board of directors elected each year, downplays the Baba's role, partly because the teacher himself wants the center to stand on its own, Maillard says.

Hari Dass comes to the center about four days a week, but does not live there. When he attends a retreat, he is described in the center's catalog as a “special guest”. Should something happen to him, the center would continue without a replacement, Maillard says.

He gets no salary and has no bank account, Maillard says. A follower provides his room and board in the Santa Cruz County community of Bonny Doon.

In the six years since it began, Mt. Madonna has branched out to encompass far more than yoga. The 1983 calendar includes workshops on the ancient Indian medical system called ayurveda, death and dying, North American Indian legends, astrology, biofeedback, watercolor painting, the Chinese version of yoga called tai chi chih, dreams, and Jewish mysticism.

The well-known physicist Fred Alan Wolf, author of Taking the Quantum Leap: The New Physics for Nonscientists and co-author of Space-Time and Beyond, leads a workshop May 13 to 15.

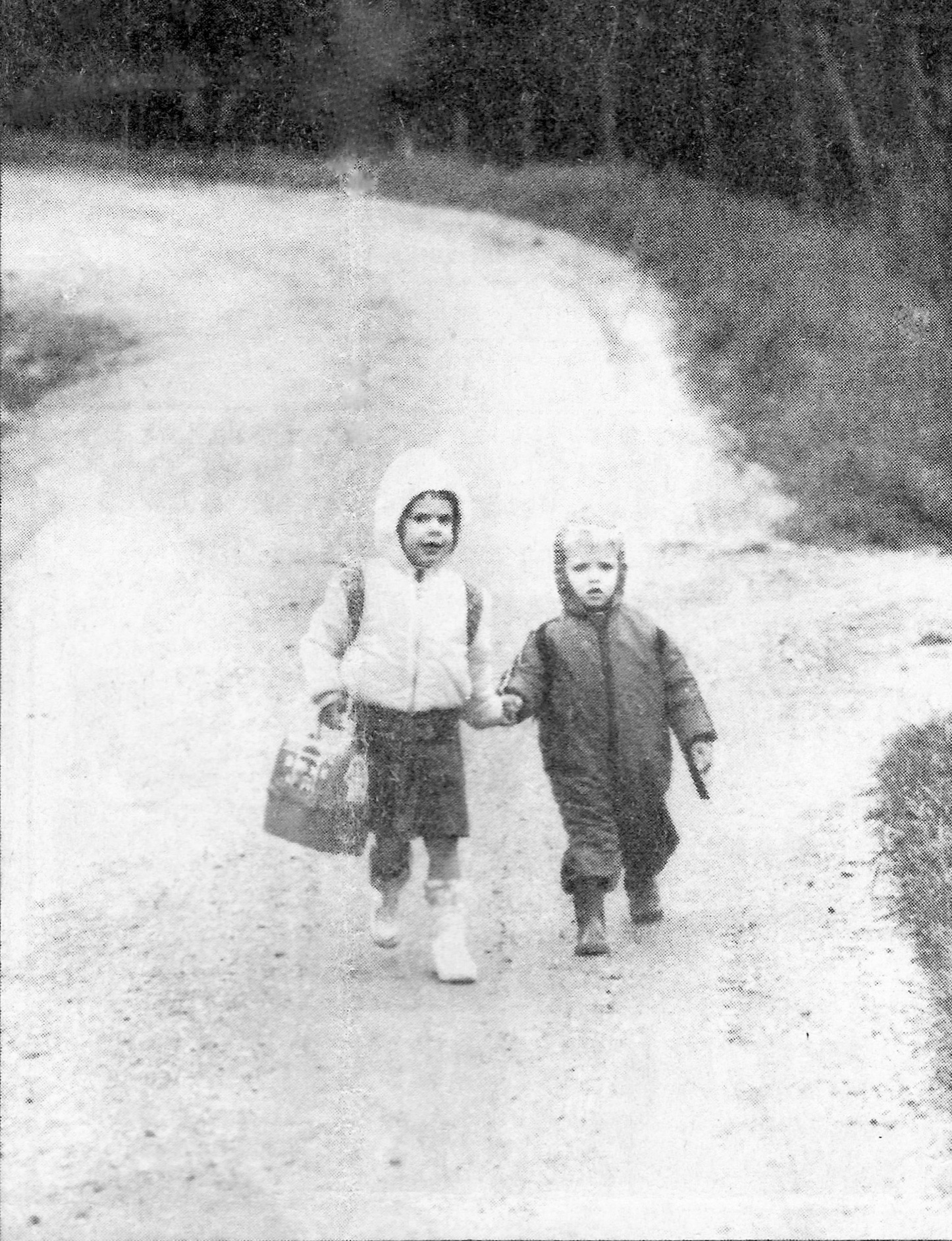

Each year, youngsters perform the Ramayana, an ancient Indian drama, before sell-out crowds in Santa Cruz.

Maillard, who supports himself from investments made after his restaurant was sold, is one of 30-35 staff members who pay a monthly room and board fee to live at the center. They answer phones, plan programs, build buildings and develop the property for free, taking off as much time as necessary to earn a living elsewhere. Only the school teachers are paid.

A college drop-out, a Ph.D. from Harvard, a construction worker - staff members value their differences. There's no rule that they must meditate or eat vegetarian food, although most choose to live that way.

“The thing you need to understand about us,” Maillard says, “is that we're fairly regular types of people.”